Kill the Indian, Christianize The Man

The efforts to help Native Americans include the campaign to ban their spiritual practices and convert their children to Christianity.

Adapted from Sacred Liberty

In 1866, the “good guys” were the Christians who merely wanted to annihilate the Native Americans’ religion. It was a strange turning point in white America’s relationship with the Indians. The Native Americans had been pushed farther west. Disease and war had dramatically reduced their numbers. The buffalo population had been so decimated that the Indian economic system had collapsed in many areas. They were cornered.

Some argued that they should be exterminated. “The more we can kill this year, the less will have to be killed the next war,” explained General William T. Sherman. “For the more I see of these Indians the more convinced I am that they all have to be killed or be maintained as a species of paupers.”

But Sherman’s views were increasingly in the minority. In his State of the Union address in 1863, Abraham Lincoln urged “constant attention” to the Indians’ well-being and a commitment to the “moral training which under the blessing of Divine Providence will confer upon them the elevated and sanctifying influences, the hopes and consolations, of the Christian faith.”

Many of those who would come to be known as “the reformers”—most of them religious Christians—believed that the Indians had just as much intelligence and skill as whites but were held back by their depraved culture. Richard Henry Pratt, a leading educator of Indians, declared: “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one. . . . In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Or, as Carl Schurz, the secretary of the interior, put it, “If the Indians are to live at all, they must learn to live as white men!”

This chapter explores a little-known episode in American history: the movement, intensifying after the Civil War, to Christianize Native Americans. The United States government banned Indian religious dances, seized land with deep spiritual significance, eliminated Indian spiritual leaders, and stripped Indian children of their religion. Many Christians still believed that religious liberty meant their own freedom to promote the one true faith. Some strange side fights erupted, as when Protestants and Catholics clashed over who got to convert the Indians. Some of them had good intentions. But the Madisonian architecture for religious freedom became useless when those in power denied, ignored, or misconstrued another group’s spirituality. Notably, those misunderstandings were exacerbated by an irresponsible media, a phenomenon that would recur in future conflicts.

Reformers

Ulysses S. Grant believed that “the whole Indian race would be harmless and peaceable if they were not put upon by the whites.”4 As an army officer, he seemed saddened by their decline: “This poor remnant of a once powerful tribe is fast wasting away before those blessings of ‘civilization,’ whisky and small pox.” In his inaugural address in 1868, he called for citizenship for the “original occupants of this land.”

Rejecting the advice of Sherman and his other Civil War comrades, Grant proposed instead a “Peace Policy.” Over the next few decades, the US government launched a number of “reforms,” often with the support of private activists, many of whom were former abolitionists. Some efforts focused on land reform; others, on teaching English and farming.

But throughout the decades there was a common theme: civilizing the Indians meant “Christianizing” them.

Grant’s first step was to bring in religious leaders who he figured would be more humane stewards. He created a Board of Indian Commissioners, which matched Christian denominations to tribes. For example, the Baptists were asked to manage the Cherokees. The Presbyterians got the Omahas in Nebraska and the Ottawas in Michigan. The Pueblos in New Mexico went to the Disciples of Christ. All in all, the Methodists oversaw fourteen Indian “agencies”; the Presbyterians, nine; and the Episcopalians, eight. The Quakers, the Baptists, and the Dutch Reformed each got five; the Congregationalists, three; the Unitarians, two; and the Lutherans, one. Even the Catholics got eight, though that wasn’t as many as they wanted. Needless to say, none of the commissioners were Indians.

Not everyone welcomed the involvement of the religious agencies. Newspapers on the frontier, where Indians continued to attack settlers and vice versa, felt that East Coast naïveté was putting their families at risk. “If more men are to be scalped and their hearts boiled,” declared the Leavenworth Bulletin, “we hope to God that it may be some of our Quaker Indian agents.” The Junction City Weekly Union seethed, “Many plans have been tried to produce peace on the border; but one alternative remains—extermination.”

Nonetheless, the policy proceeded, with a mission of erasing the existing Indian culture and substituting something far better. “As we break up these iniquitous masses of savagery,” explained Merrill Gates, chairman of the Board of Indian Commissioners (and former president of Amherst College), “as we draw them out from their old associations and immerse them in the strong currents of Christian life and Christian citizenship, as we send the sanctifying stream of Christian life and Christian work among them, they feel the pulsing life-tide of Christ’s life.”

There seemed to be only the dimmest recognition that the Indians already had religions of their own. Occasionally the reformers would refer to their “heathenism” and “superstition,” but there certainly was no sense that the Indians had a coherent, deeply embedded religious order, let alone one that might be providing them health, morality, inspiration, or meaning.

What were the religions that the reformers tried to repeal and replace? It’s hard to generalize, as there were hundreds of Native American religions, each different. But they shared a common belief that there was no clear separation between the spiritual and physical worlds. Spirits inhabited animals, land, the sun and the moon, and in some cultures these spirits were associated with a larger deity, such as the Lakota’s Wakan-Tanka, or the “Great Mysterious.”10 They often practiced life cycle rituals that combined religious and ceremonial elements. During vision quests they communicated directly with the supernatural, sometimes in the form of an animal. They taught their children myths, songs, dances, and rituals, each pregnant with spiritual meaning. “In the life of the Indian there was only one inevitable duty—the duty of prayer—the daily recognition of the Unseen and Eternal,” wrote Charles Eastman, a Native American physician and author. “His daily devotions were more necessary to him than daily food.” Scholar David Wallace Adams summarized:

Traditional Indian cultures were so thoroughly infused with the spiritual that native languages generally had no single word to denote the concept of religion. It would have been incomprehensible to isolate religion as a separate sphere of cultural existence. For the Kiowa, Hopi, or Lakota, religion explained the cosmological order, defined reality, and penetrated all areas of tribal life—kinship relations, subsistence activities, child raising, even artistic and architectural expression.

That all had to be purged, along with other elements of culture, if the Indians were to prosper. The assimilation efforts were, US Commissioner of Indian Affairs Francis Leupp proudly explained, “a mighty pulverizing engine for breaking up [the last vestiges of] the tribal mass.”

“Take Their Children Away”

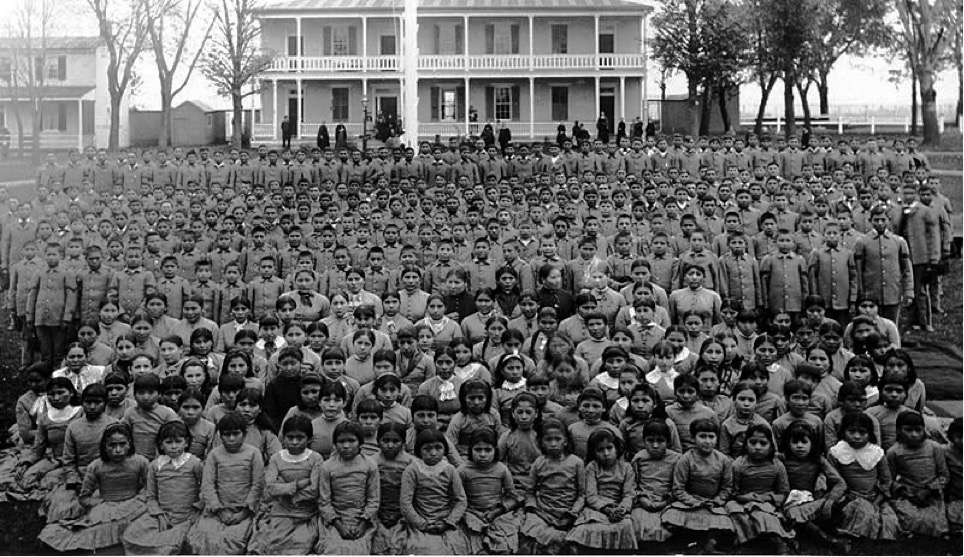

Education became one of the key arenas for conflict with Native Americans, as it would be in the future with Catholics, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Jews. The idealistic reformers of the post–Civil War era viewed schools as the heart of the “pulverizing engine” that would help the Indians. One needed to remove the children from their parents, the pollutions of tribal life, and their religion. “Education cuts the cord that binds [Indians] to a Pagan life, places the Bible in their hands, substitutes the true God for the false one, Christianity in place of idolatry . . . cleanliness in place of filth, industry in place of idleness, self-respect in place of servility, and, in a word, an elevated humanity in place of abject degradation,” read an 1887 report from agents overseeing the Dakota reservations. They tried to get the children young. “All those concerned with the school agree that the smaller the children are taken in the better and faster they learn,” reported Father Bandini of the St. Xavier Mission Boarding School on the Crow Reservation in Montana.

What evolved during this period was a multilayered system that included day schools and boarding schools on reservations and boarding schools far from home. Some were run by religious groups and some by the government. By 1890, 75 percent of Indian children in school were in immersion programs, according to Jon Reyhner and Jeanne Eder in American Indian Education. Senator George G. Vest explained that “it is impossible to do anything for these people, or to advance them one single degree until you take their children away.”

The most acclaimed was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, a government-backed boarding school created by General Richard Henry Pratt. When it came to his educational philosophy, he ex- plained, he was like a Baptist: “I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization and, when we get them under, holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked.”

On the plus side, the boarding schools taught the Native American children to read and write, gave them some employable skills, and offered them cultural opportunities, such as playing musical instruments or participating in sports. Olympian Jim Thorpe came out of the Carlisle football team.

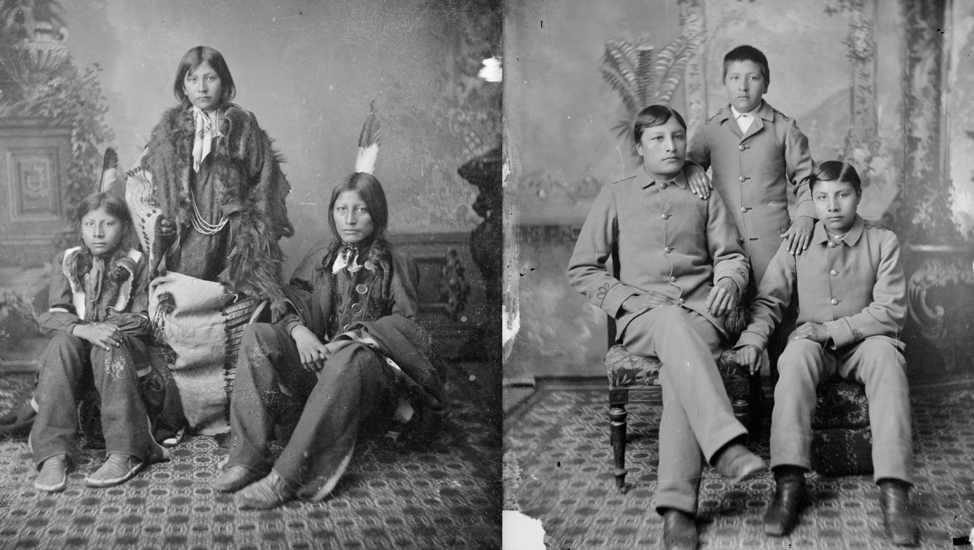

But the approach of Carlisle and other similar schools left many scars. The children were taught to hate their culture. First, their hair would be cut off. The Sioux writer Zitkála-Šá recalled hiding under a bed. “I remember being dragged out, though I resisted by kicking and scratching wildly. In spite of myself, I was carried downstairs and tied fast in a chair. I cried aloud, shaking my head all the while, until I felt the cold blades of the scissors against my neck, and heard them gnaw off one of my thick braids. Then I lost my spirit.” Luther Standing Bear, a Sioux who went to Carlisle, remembered crying after his hair was cut: “I felt that I was no more Indian but would be an imitation of a white man.”

Then the schools changed the children’s names. They emerged with names like Mary, Joseph, Aloysius, Francis Xavier, Hildegarde Fischer, Julius Caesar, and Henry Ward Beecher.

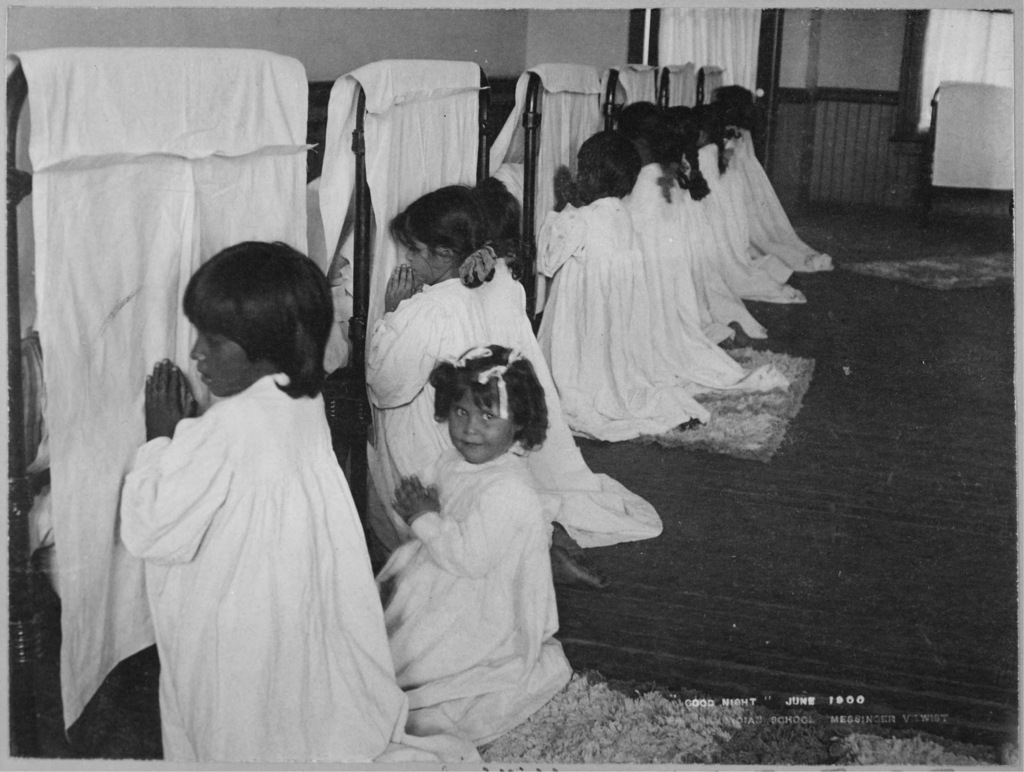

Discipline was more like that in the military, or in some cases prison, than a school. A Hopi woman recalled being whipped after she and her friends left the school’s grounds to pick apples nearby. A Lakota woman recounted a tale from her grandmother about a punishment she received for not paying attention in church.

Instead of praying she was playing jacks. As punishment they took her to one of those little cubicles where she stayed in darkness because the windows had been boarded up. They left her there for a whole week with only bread and water for nourishment. After she came out she promptly ran away together with three other girls. They were found and brought back. The nuns stripped them naked and whipped them. . . . Then she was put back into the attic—for two weeks.

Schools severely punished “deserters,” as they were known. The Chilocco Indian Agricultural School in Oklahoma had eighty escapes in three months in 1925.25 Keams Canyon Elementary School, in modern-day Arizona, padlocked the dormitory’s doors at night to prevent escape. Some Hopi boys protested by defecating on the floors. At the Chilocco School, the head of the school responded to word that students were planning to run away. “Telling them to undress, he handed each one a blanket, trans- ported them ten miles out into the prairie and left them.” At the Williams Lake School in British Columbia, nine children attempted suicide by eating water hemlock after receiving severe beatings. The most amazing runaway story happened at Fort Mohave in Arizona: a group of kindergartners took a large log and used it as a battering ram to break down the jail door, releasing the students who were being punished there.

Indian parents had mixed feelings. Many had concluded that, sadly, the Indian way of life was dying and that to succeed, their children would need to learn the ways of the whites. The father of Charles Eastman, who would go on to become a doctor, praised the white man’s emphasis on the written word. “I think the way of the white man is better than ours, because he is able to preserve on paper the things he does not want to forget.”

But as shocking stories came back from the schools, many parents changed their mind. The most terrifying news: the children were dying at alarming rates. Often cramped and unhygienic, the schools were breeding grounds for disease. Of the 640 students who attended Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute over thirteen years, 110 died. In 1890, sixty- eight children died of scarlet fever. The agent at Fort Apache, Arizona, C. W. Crouse, reported that the deaths of several children had prompted a rebellion among parents: “I was compelled to resort to force, and every pupil was returned to the school by the police.” A Spokane tribe saw six- teen of the twenty-one children they’d sent to eastern schools die in 1891.

The chief complained that the schools didn’t have the decency to send the bodies back. “If I had white people’s children I would have put their bodies in a coffin and sent them home so they could see them. . . . They treated my people as if they were dogs.” Each boarding school had a cemetery for the children.

The government required the students to be in these schools and sent Indian police out to round up truants. The agent to the Mescalero Apache, in what is now New Mexico, in 1886 wrote:

Everything in the way of persuasion and argument having failed, it became necessary to visit the camps unexpectedly with a detachment of police, and seize such children as were proper and take them away to school, willing or unwilling. Some hurried their children off to the mountains or hid them away in camp, and the police had to chase and capture them like so many wild rabbits.

This unusual proceeding created quite an outcry. The men were sullen and muttering, the women loud in their lamentations, and the children almost out of their wits with fright.

S. J. Fisher, the agent in modern-day Idaho, reported that he’d had “to choke a so-called chief into subjection” to get his children. A group of Hopi Indians were sent to military prison on Alcatraz in part for refusing to surrender their children. The annual report of the US Department of the Interior in 1901 cheerfully detailed the government’s good work.

Gathered from the cabin, the wikiup, and the tepee, partly by cajolery and partly by threats; partly by bribery and partly by force, they were induced to leave their kindred to enter these schools and take upon themselves the outward appearance of civilized life.

In 1893, Congress authorized the agents to deny food rations to families that resisted sending their kids to school. Indian parents resisted in part because they realized that the schools were converting their children. Spotted Tail, a leader of the Brulé Lakota at the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, sent four of his children to Carlisle. A year later, he saw his kids shorn of their hair and learned that they’d been baptized. Appalled, the Brulé parents pulled all thirty-four children out of the school. Albert Kneale, who worked as principal of a boarding school, reported frankly that students “were taught to despise every custom of their fore- fathers, including religion.”

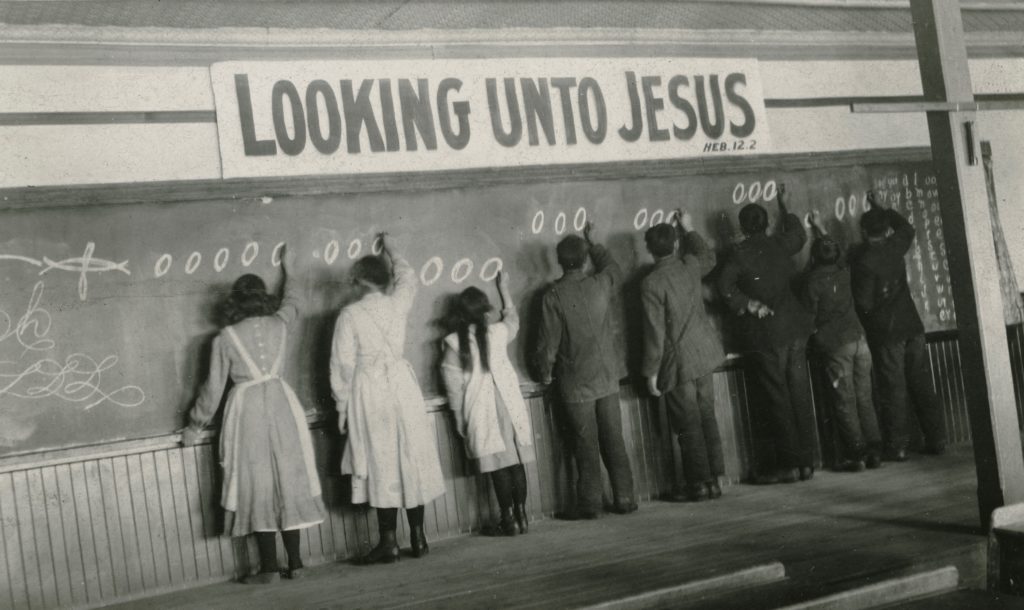

Although all of the schools banned expressions of Indian religions, they differed in their approaches to teaching Christianity. The schools run by religious missions instilled Christianity throughout the day. At the St. Xavier Mission Boarding School on the Crow reservation, the Catholic instruction was pervasive. The kids stayed year-round; parents could visit on Sundays for one hour. The children had daily morning Mass at 6:30 a.m. They were taught academic, vocational, and religious subjects during the day and also had time to learn to play the organ, violin, and other instruments. At 8:00 p.m. they had prayer time. Throughout the day, the kids at St. Xavier—like the children at most of the schools—did unpaid menial labor, such as washing clothes, to help run the school. On Sunday there was a full Mass. They also celebrated Ash Wednesday, Good Friday, Easter, Pentecost, and Christmas.

The teachers struggled to sell the Crow on certain elements of Catholic theology.

Scholar Karen Watembach describes how the Jesuit missionaries who ran St. Xavier first had to convince the Crow that there was such a thing as “sin,” which was not a concept in the Crow religion, for “unless the Crow people had heard of sin they would have no need of a redeemer.” The Crow believed that bad behavior was to be expected from humans but that the person was “not condemned unless an act had brought disgrace to the whole family. Then the person was shunned.” They were confused by the idea that God would make people in his own image and then have them be steeped in sin. Teachers also had to convince the Crow about the existence of hell. One day, the priest, Father Prando, drew a picture to show where the Indians had gone before the missionaries had arrived— two small circles for heaven and hell and a large one for purgatory. A Crow leader, Plenty Coups, who had invited the Jesuits to the reservation, pointed to the large circle and said, “That’s where I want to go, where most of my people are.”

Zitkála-Šá recalled being introduced to the concept of the devil. The Sioux taught about bad spirits, she wrote, but there was no “insolent chieftain” attempting to organize the evil spirits against God. “Then I heard the paleface woman say that this terrible creature roamed loose in the world, and that little girls who disobeyed school regulations were to be tortured by him.” One night, she dreamed that a yellow-eyed devil had invaded her home. The next morning, she opened her Stories of the Bible to the picture of the devil and scratched out his eyes.

The Crow discovered that their method of prayer, which was personal and improvisational, was all wrong. They needed to recite the Catholic prayers word for word, they were told. Bible stories supplanted the “superstitious” Crow tales. For example, the story of how Old Man Coyote created the earth from a lump of clay at the bottom of a pond was replaced with the “true” Genesis story of God creating the heavens and the earth and then making a woman out of Adam’s rib. Mary Crow Dog, a Lakota writer, recalled that as a girl at a Catholic boarding school, “I learned quickly that I would be beaten if I failed in my devotions or, God forbid, prayed the wrong way, especially prayed in Indian to Wakan Tanka, the Indian Creator.”

The government schools—the ones not run directly by religious organizations—had a somewhat different approach. They emphasized religion on the weekends rather than during the week. There was a sermon each Sabbath, Sunday school, and a weekly prayer meeting conducted by students. They used the Protestant Bible and hymns. Protestant youth organizations such as the Young Men’s Christian Association were active. The “non-sectarian schools,” wrote scholar Francis Paul Prucha, “were in fact Protestant schools.” An 1899 report from the superintendent of Indian schools offered assessments of the religious instruction at the schools she visited. “Religious exercises are conducted regularly,” “religious training is carefully given,” “the religious welfare of the children is carefully looked after,” and “at each school there is a force of faithful, Christian teachers,” she reported.

Reformers routinely advocated “Christian civilization.” That wasn’t just a religious term but included cultural elements such as speaking English, wearing proper white-man clothes, and abandoning hunting as a vocation. Indian schools were required to celebrate the “discovery” of the New World each Columbus Day. When, in 1892, Richard Henry Pratt brought 322 of his students to march in a Columbus Day parade in New York City, the banner they carried read “Into Civilization and Citizenship.” A similar parade in Chicago prompted the Springfield Union to note that “the students of Carlisle PA, Indian school represented the savages Columbus found. But instead of appearing as savages, they marched in their present character as intelligent, well-dressed and well-bred young men.” They also celebrated Thanksgiving and Christmas.

When children died at boarding schools, they were given Christian burials. Pratt seemed to think he was comforting a parent, Chief White Thunder, when he informed him that his child, Ernest, had died but assured him that he would be given a “white” burial.

I had them make a good coffin and he was dressed in his uniform with a white shirt and nice collar and necktie. . . . And the minister read from the good book and told all the teachers and the boys and girls that some time they would have to die too. He told them they must think a great deal about it and they must be ready to die too. . . . He explained that they emphasized the Bible because “it is that book which makes the white people know so much as they do.”

The policy of having the government fund religious schools ended in the late 1890s for reasons that were in some ways darkly comical. Conflict arose over matters of religious tolerance. No, members of Congress did not suddenly realize that forcing Indian children to attend government- financed Christian schools violated their religious freedom. Rather, a fight broke out between Protestants and Catholics over how to best Christianize the Indians. The Catholics complained that Indian children were being assigned to schools run by the Protestant denominations. The First Amendment, they said, guaranteed the parents’ right to choose . . . be- tween Christian religions. “The Indians have a right, under the Constitution, as much as any other person in the Republic, to the full enjoyment of liberty of conscience,” declared a statement from the Catholic leaders of Oregon.

“Accordingly, they have the right to choose whatever Christian belief they wish, without interference from the government.”

At first, the Protestant denominations enthusiastically supported the government’s funding. But then a funny thing happened. Over time, more and more of the money went to Catholic organizations, in part because they had been doing extensive missionary work with Indians for much longer than the Protestants and were more adept at setting up schools. By 1889, 75 percent of the funds for the fifty religious schools was going to Catholic institutions. Catholics also raised money privately to open more schools, seeing them as weapons in a missionary battle, in which their rivals were not the Indians but the Protestants. “If we do this, we do an immense deal of good, get the Indians into our hands and thus make them Catholics,” wrote the director of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, which coordinated these efforts. “If we neglect it any longer, the Government and the Protestants will build ahead of us schools in all the agencies and crowd us completely out and the Indians are lost.”

With the Catholics ascendant, the Protestant organizations began pulling out of the program and decrying the system of government-funded religious schools as—wait for it—a violation of the separation of church and state. As during the battles over the Bible in schools, they decided they’d rather go secular than have the Catholics be the ones to teach about God. Thomas Jefferson Morgan, the commissioner of Indian affairs, in 1889 proposed a system of universal “non-sectarian” government-run schools, which would effectively reduce the role of the churches. He attacked the Catholic schools as “un-American, unpatriotic and a menace to our liberties . . . a corrupt ecclesiastical-political machine masquerading as a church.” Morgan, a Baptist minister, referred to the Catholic Church as “an alien transplant from the Tiber . . . recruiting her ranks by myriads from the slums of Europe.”

The Catholics rightly interpreted the effort to support only nonsectarian schools as an attack on them. “[The] sole aim and purpose is to drive the Catholic Church out of the Indian educational and missionary field,” wrote Joseph A. Stephan of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions in 1893. And the Protestants had a lot of nerve, given their own shoddy record of teach- ing good values. “Morals are said to be very low in that school,” wrote Father J. B. Boulet to the editor of Catholic News when students were slotted to be transferred from a Catholic school to the government-run Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon. “Too much freedom among the sexes and followed by many breaches against chastity. Graduates of this school are generally proud, haughty—polished heathens.”

Some Catholics even wondered whether it might be better to let the Indians languish in their heathenism than to have Protestant teachers draw them away from the Catholic Church’s schools. “Is it possible that we have labored so long and so diligently among Indians only to bring up them and their children a greater damnation? I fear it might have been better for them never to have known the truth, than after having been incorporated in the Church to be perverted and corrupted.”

This issue became part of the 1892 presidential election, the first in which a candidate, Democrat Grover Cleveland, openly campaigned to gain the support of Catholic voters. Catholic missionary groups charged the Indian commissioner and the sitting president, Republican Benjamin Harrison, with being anti-Catholic. The Catholic Herald declared that the Republicans, “led by bigots,” had “robbed the Catholic Indians of their only treasure, their faith.” By “their faith,” of course, they meant their newfound Catholicism, not the Indian spiritual practices that the Catholicism had erased. Nonetheless, Congress gradually moved away from the highly religious mission-led schools to the somewhat religious “government schools.” In 1897, Congress ended the appropriations for religious schools.

Not all Indians disliked these schools. Many said that becoming Christian changed their lives for the better, especially given the poverty on the Indian reservations, devastated as they had been by disease, war, and the disappearance of the buffalo. “This was my great good fortune,” said Jason Betzines, who had gone to the Carlisle school, “to make something of myself, to lift myself to a more useful life than the old pitiful existence to which I had been born.” Thomas Alford had been told by tribal elders to learn skills and English but resist the efforts to purge him of his religion: “Then came the conviction of truth, the dawn of knowledge, when I knew deep in my soul that Jesus Christ was my savior.” Thousands of other students who converted to Christianity gained great sustenance from it. And it’s impossible to know how many of those conversions would have happened anyway through voluntary exposure.

But while the schools’ leaders viewed those conversions as a triumph, the students’ parents mostly viewed them as an assault. Their growing resistance was fueled, wrote historian David Wallace Adams, by their realization that the schools expected their children not only to sever their bonds with their families but also to “abandon their ancestral gods and ceremonies.”

The Ban on Sacred Dances

In 1883, the commissioner of Indian affairs, Hiram Price, issued what amounted to a full-scale attack on Native American religion. First, the government banned a variety of Indian dances, including the Sun Dance, the Scalp Dance, the War Dance, and “all other so-called feasts assimilat- ing thereto.” Those guilty of the crime of unlawful dancing would lose rations for ten days. On the second offense, they could lose rations for thirty days. The third time, they could go to prison for ten to thirty days.

Second, it criminalized the role of “medicine men,” who acted as spiri- tual leaders in most tribes.

Third, it banned an Indian mourning ritual in which families would destroy property of the deceased.

All of these measures were justified in nonreligious terms (as attacks on Mormonism had been, and attacks on Jehovah’s Witnesses would be, decades later). But as we’ll see, each policy attempted to uproot important elements of religious (as well as cultural) practice for most Indians. The Christian majority had great difficulty understanding how dances or the mumbo jumbo of medicine men could be viewed as akin to worshipping in church or taking sacraments. Ignorance about the nature of unfamiliar spirituality blinded them to the notion that they were guilty of an assault on religious freedom.

Let’s start with the mourning ritual. Grieving Indian families in the Dakota Territory traditionally gave away some of the deceased’s property “to prove their deep sorrow.” The Indians believed that spirits some- times linger, and giving away property would ensure that they moved on. They used other life milestones as occasions to give away belongings as well. This disgusted government officials and missionaries who worried that without a sufficient appreciation of private property, the Indians would never advance from their barbaric hunter-gatherer state. A poster that missionaries gave to Indians to put on their walls offered this bit of advice: “Believe that property and wealth are signs of divine approval.” But to the Indians, the devaluation of property was the whole point. “It was our belief that the love of possessions is a weakness to be overcome,” Charles Eastman wrote. “Its appeal is to the material part, and if allowed its way it will in time disturb the spiritual balance of the man.”

The government’s efforts largely succeeded. “This pernicious custom is almost wholly broken up,” the authorities reported.

As for the ban on medicine men, one must remember that in Indian culture they were at once clergy, prophets, and health-care workers. They frequently mixed prayers, herbs, predictions, and psychotherapy. Imagine if the government today were to issue a ruling banning the “the usual practices of so-called ministers or pastoral counselors.” Medicine men were highly influential and therefore viewed as obstacles to the program of civilizing and Christianizing the Indians. The new rules required that any person who practiced “the arts of the conjurer to prevent the Indians from abandoning their heathenish rites and customs” should be imprisoned for at least ten days “or until such time” as he “will forever abandon” his practices.

Perhaps the most consequential element of the crackdown was the ban on dances. Though dances varied by tribe, they were invariably an important part of their spiritual practice, a way of deploying the spirits for essential purposes and creating tribal cohesion.

The Sun Dance, for instance, was used to summon spiritual help for those going on hunts or into battle or to beseech the Great Spirit for a good harvest. The preparation involved fasts, property giveaways, songs, and other elements over several days. Its most controversial feature was self-torture. The dancers sometimes cut themselves, and in some tribes the practice became gruesome—slits were cut into the skin, and straps were passed through them. The pain and loss of blood made it more likely that they would have visions. The government banned the dance, which had a particularly demoralizing effect on the Sioux, according to historian Robert Utley:

No longer could they appeal directly to Wi [the Sun] for personal power and assistance. No longer could they experience the pervading sense of religious security that came only from the Sun Dance. . . . The Sioux had been dealt a shattering emotional blow, and their lives began to seem like a great void.

Throughout America, police were told to break up the dances. In 1885, James McLaughlin, the agent at Standing Rock Indian Reservation in modern-day North Dakota and South Dakota, proudly reported:

“Three years ago the ‘tom-tom’ (drum) was in constant use, and the sun dance, scalp dance, buffalo dance, kiss dance, and grass dance, together with a number of feast and spirit dances, were practiced with all their barbaric grandeur; but all these are now ‘things of the past.’”

The most catastrophic conflict arose over a newly created ritual called the Ghost Dance. It was promoted in the 1890s by a Northern Paiute prophet named Wovoka, who in 1889 reported that he had died and traveled to heaven, where God taught him a new dance and gave him a set of messages. If the Indians led good, honest, peaceful lives, he said, the dead would come back to life and the land would once again be full of buffalo and game. Illness and death would be banished. And then there was the part that drew special attention from the non-Indian population: if the dances were performed properly, a great cataclysm, perhaps a flood or an earthquake, would wipe out the whites. His message was similar to the millennial promise of Mormons, evangelical Christians, and many other faiths that look forward to the End of Days and the advent of a new Kingdom of God—with two differences: a dance would trigger the arrival of paradise, and white Christians would have no place in it. By one account, Wovoka believed that God’s vision would not spare the Indians’ tormentors:

“When Old Man [God] comes this way, then all the Indians go to mountains, high up away from whites. Whites can’t hurt Indians then. Then while Indians way up high, big flood comes like water and all white people die, get drowned. After that, water go away and then nobody but Indians everywhere and game all kinds thick.”

He told his followers to dance for four consecutive nights and then repeat this six weeks later. The ritual was preceded by a purification fast or sweat lodge ceremony. The dancers wore special shirts—the yoke was sky-blue, and the rest was decorated with images of the moon, stars, eagles, crows, and buffalo. These “ghost shirts” were said to repel bullets. They danced in a circle, hand in hand, gradually increasing the pace. As they glided around, dancers called out the names of their dead relatives, throwing dirt in their hair to signify grief. Excitement grew, and those who left the circle, said historian Rani-Henri Andersson, “fell to the ground with trembling limbs and lay motionless, seemingly dead.”

Leaders from the Sioux, Shoshone, Arapaho, Cheyenne, and other tribes across the country traveled by train to present-day Nevada to size up Wovoka. Each recounted the meetings differently. Sometimes Wovoka was described as a prophet. At other times, he was Christ returned. In another account, Jesus was an Indian who had been driven from Earth by immoral whites. “God blamed the whites for his crucifixion,” the story went, “and sent his son Wovoka back to the Indians, since the whites were bad.”

Word of Wovoka and the dance spread from tribe to tribe, aided by the telegram and the railroad. By 1890, at least thirty tribes participated, and it had become a most unusual phenomenon: a pan-Indian ceremony.

Remarkably, most accounts of Wovoka contained strong Christian elements. Several witnesses reported seeing wounds in Wovoka’s palms. Fast Thunder, a Christian who performed the Ghost Dance, recounted:

“As I looked upon his fair countenance, I wept, for there were nail prints in his hands and feet, where the cruel white men had fastened him to a large cross. There was a small wound in his side also, but as he kept his side covered with a beautiful blanket of feathers, this wound could only be seen when he shifted his blanket.”

Rather than viewing the Christian elements as a sign that their theology was penetrating Indian consciousness and declaring victory, the missionaries saw the telltale signs of Satan. The devil, explained one missionary, had cleverly made a beguiling “combination of the old heathen dance and the idea of a Messiah brought in by a gleam of Christianity.”

After visiting one of the dance camps at White River, Father Florentine Digman reported that there was no uprising afoot but that the Indians were enraged that the agents had threatened to cut off their rations if they kept dancing.

“Obey [the] order then and quit dancing,” the priest advised. “Why after all are you bent on dancing?”

“This is our way of worshipping the Great Spirit,” responded one of the Indian leaders.

“I fear it is another spirit that leads you astray.”

The Indian pointed out that the Christian missionaries couldn’t even agree with each other over the right way to pray. “Let us alone then, and let us worship the Great Spirit in our own way.”

Government agents were less sanguine; they feared that the Ghost Dances would lead to violence. It’s important to understand the context. The Indians, especially the Sioux Indians in the Plains states, were in dire straits. The government had recently taken a big chunk of land to give to white settlers and the railroads, cutting their reservation in half. The Indians had so little land that they could no longer base their economy on hunting. The property they had left was difficult to farm, and 1890 saw a horrible drought. “The Indians were brought face to face with starvation,” wrote James Mooney, a government official who surveyed the area. The government’s response: to increase the Indians’ incentives to farm, they cut their rations.

In August 1890, two thousand Sioux gathered at White Clay Creek (near Pine Ridge in modern-day South Dakota) to perform the Ghost Dance. The government agent, H. D. Gallagher, sent twenty police officers to break them up, but the effort was unsuccessful. Partisan politics inflamed the situation. A South Dakota newspaper said that Gallagher, a Democratic appointee, had been too soft, allowing the Indians to “leave their children and stock to care for themselves and spend their time in dancing and wild religious orgies.” Gallagher was soon replaced by a Republican, Daniel F. Royer, who tried to convince the Indians to stop. The leaders laughed at him and told him they would “keep it up as long as they pleased.” A few weeks later, a panicked Royer reported that almost thirteen hundred Indians were joining in the dances. He telegrammed Washington, DC, repeatedly, pleading for troops. A massive Indian uprising was brewing, he wrote. “Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy. We need protection and we need it now.” In October there were almost daily Ghost Dances on the four Lakota reservations.

Press coverage mostly made matters worse, suggesting or asserting, with no evidence, that the Ghost Dances were a part of Indian war prepa- rations. By mid-December there were seventeen correspondents in the area. The Washington Post and Chicago Tribune quoted a military source who said that the “incantations and religious orgies” would soon lead to trouble. The New York Times ran an article with the headline “How the Indians Work Themselves Up to a Fighting Pitch,” which explained, “The spectacle was as ghastly as it could be: it showed the Sioux to be insanely religious.” A Washington Post piece blamed the whole thing on the Mormons. Relying on military sources, the press accounts tended to exaggerate the number of potential warriors, printing estimates of fifteen thousand to twenty-seven thousand when the number was probably more like five thousand. More to the point, extensive historical research has found that the dancers were not planning an uprising. Settlers became alarmed and started leaving the area.

The news accounts also reflected the view that the real driver of the dancing was Sitting Bull, the renowned leader then living at Pine Ridge. That wasn’t true. Sitting Bull had heard of the dancing late in the game and was reportedly ambivalent about it. But as the man who had defeated Custer, Sitting Bull—still an ardent opponent of the whites—was the most frightening Native American alive, and he was an easy villain for reporters intent on hyping a dramatic showdown. Royer pushed that line too and demanded that Sitting Bull be arrested.

In Washington, President Benjamin Harrison was weighing political as well as military factors. Harrison and the Republicans, argues historian Heather Cox Richardson, figured that taking military action would convince the white settlers that the government had their back. The president told the secretary of war to intervene.

On December 15, a group of Indian policemen at Standing Rock Indian Reservation moved to arrest Sitting Bull, but the operation went horribly wrong. A scuffle ensued, and an Indian policeman shot Sitting Bull in the head. As word spread, Indians exited the area.

Some of the fleeing Indians—a wagon train of about three hundred men, women, and children from the Miniconjou tribe—were stopped by US Army troops and ordered to return with them to their camp near Wounded Knee Creek.

The next day, on December 29, the Indians were told to turn in their guns. Some were surrendered, but the soldiers believed there were more, so they went from tent to tent, pulling out knives and other weapons. The soldiers, now about five hundred strong, were tense, having read news- paper articles about how the Ghost-Dancing Indians were preparing for war. One Indian—some say he was deaf, others that he was crazy—raised his gun in the air, declaring in Lakota that he had paid good money for the new Winchester and was not about to give it up. The soldiers grabbed him, and a shot was fired into the air.

Hundreds of soldiers opened fire on the Indians. Two-pound shells from the Hotchkiss cannons poured down. In just a few minutes, two hundred Indian men, women, and children were dead, along with twenty-five soldiers, most of whom were killed by friendly fire. Women and children who tried to flee the scene were shot as they ran. Bodies were found almost two miles away from the scene. One witness reported seeing a newborn infant nursing from its dead mother’s breast. Another recalled: “I saw a boy and a girl, probably 8 or 10 years old, running from the field in a southeast direction toward the creek, and I saw two soldiers drop down each on one knee, and taking a knee and elbow rest of their pieces, kill these little children who, when hit, carried by the momentum of running, went rolling over.”

After the massacre, snow buried the dead. A cleanup party was sent on January 1, 1891, but the bodies were frozen under the bloodstained white covering. Yet several babies were found alive, lying beside their dead mothers. Other victims were frozen in grotesque positions where they had fallen. Some children were wearing their school uniforms. The soldiers stripped many of the bodies naked—in part to get the “ghost shirts” as souvenirs—and 146100 frozen bodies were dumped into a mass grave.

Most of the public reaction was positive. Twenty of the soldiers were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

It would be an exaggeration to say that the massacre at Wounded Knee was primarily an act of religious violence. Economic, social, and political factors helped fuel Indian passions and white paranoia. But the whites’ inability to see the Ghost Dance as a religious phenomenon—thanks to their deep ignorance of, and arrogance about, Native American spirituality— led them to wildly misinterpret its significance. They also underestimated the rage that suppressing it would cause. Whites didn’t view their war on the Ghost Dance as an assault on religious freedom, but the Indians surely did.

No history of the assault on American Indian religion is complete without a consideration of the spiritual impact of the loss of land. Of course, settlers took land from the Indians mostly for reasons unrelated to religion. But Native American religion is intimately connected to the land in ways that Abrahamic religions are not. Indians have occupied North America for thousands of years. When Moses was leading the Hebrews out of Egypt, Indians were already deeply ensconced in North America. Native American spirituality is grounded in a belief that all nature is imbued with life spirit. But tribes also bonded to specific areas. Some were the birthplaces of gods; others were places where people could commune with spirits. The Navajo point to specific mountains from which their people arose from the underworld. The Hopi believe that the emissaries of the gods reside in the San Francisco peaks. The Tsistsista and Lakota believe that humans were created within the Bear Butte area of the Black Hills of South Dakota. When a government agent tried to convince the Shahaptian to switch from hunting and fishing to farming, Smohalla, their chief, explained:

“You ask me to plow the ground. Shall I take a knife and tear my mother’s bosom? Then when I die she will not take me to her bosom to rest. You ask me to dig for stone. Shall I dig under her skin for her bones? Then when I die I cannot enter her body to be born again. You ask me to cut grass and make hay and sell it, and be rich like white men. But how dare I cut off my mother’s hair?”

Every forced removal from an ancestral homeland left a profound spiritual wound.

While the religious harm was often an unintentional side effect of other agendas, sometimes it was the point. John Wesley Powell, the noted explorer who became the head of the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology, argued that the government should try to shatter the Indians’ “attachment to his sacred homeland.” He advised the secretary of the interior as follows:

When an Indian clan or tribe gives up its land it not only surrenders its home as understood by civilized people but its Gods are abandoned and all its religion connected therewith, and connected with the worship of ancestors buried in the soil: that is, everything most sacred to Indian society is yielded up.

Although the attacks on the religious freedom of Native Americans and slaves are the most extreme in American history, even here lessons can be learned about the broader trajectory of religious liberty.

When Americans are inclined to deprive a group of its religious freedom, they often deny that they are suppressing an actual religion. The literature of the period is full of comments such as that of Wilkinson Call, a US senator from Florida, who declared that to promote morality, the Indian children should be “put under the guardianship of religion.” Religion in this case meant Christianity, written on the blank slate of a Native American soul.

While those attempting to deprive the Mormons and Catholics of their religious rights (and, later, Jews and Muslims) had to go through contor- tions to racialize their differences, Native Americans were already viewed as savages. As with slaves, the public commitment to religious liberty was not sufficiently strong to overpower other forms of bigotry. Rights were very much alienable.

Whites did not embrace religious freedom as a universal right, nor did they feel that their own rights were defined by how they treated Indians. The majority figured that one benefit of religious liberty was having the latitude to convert others, sometimes forcibly. In some cases, they be- lieved the Indians were not only mistaken in their beliefs but also guided by Satan. These cases pose a particular challenge to the Madisonian model for religious competition. It’s hard to maintain free market sensibility— may the best religion win!—when one group sees the other as animals or humans led by the forces of darkness.

Few religious leaders defended the Indians. Those advocating religious liberty meant something quite limited: the freedom to choose between Protestantism and Catholicism. The agent at the Siletz Indian Agency in Oregon in 1889, Beal Gaither, said with sweet pride that he had “endeavored to secure the Indians the privilege of religious liberty.” His proof: “During the short time I have been in charge there have been about forty members taken into the Methodist Church and about the same number have been baptized to the Catholic Church.”

The Native American experience again illustrates the interconnected- ness of our rights. Indians did not have the right to vote and therefore could not bring political pressure to bear on their situation, as Mormons, Catholics, and Jews eventually did.

The treatment of the Indians also reveals the importance of the press— this time in undermining religious freedom. By failing to understand or explain the genuine spirituality of Native Americans, the media enabled Americans to default to their fears.

Interestingly, the Native Americans began to make more progress in protecting their spiritual lives when they cast their appeals in the language of religious freedom. When the commissioner of Indian affairs limited dancing during the Fourth of July celebrations of the Blackfeet in Montana in 1917, an Indian representative named Wolf Tail used analogies that the whites would understand. “These gatherings are to us as Easter is to white people. We pray, and baptize our babies only instead of water we paint them.” Protesting limits placed on their ceremonies in 1916, leaders of the Ojibwa of the Red Lake Indian Reservation in Minnesota explained, “The beating of the Drum is simply an accompaniment to the songs of praise uttered by the congregation,” just as “in every Church of the White man a Piano or Organ is found for the same purpose.” Thus they demanded the freedom to practice “the Chippewa religion.” As scholar Tisa Wenger put it, “The demand for religious freedom relied on re-interpreting indigenous practices in Christian terms.”

Though Native Americans still must fight for their religious rights, there was a seismic shift for the better in the 1930s. President Franklin Roosevelt appointed as his commissioner of Indian affairs a man named John Collier, who had a dramatically different attitude. Collier declared point-blank that the Bureau of Indian Affairs had been “making it a crime to worship God.” In 1934, he issued Circular No. 2970, which ended most of the government’s repressive policies.

Congress did eventually codify the religious freedom rights of the Native Americans. The American Indian Religious Freedom Act decreed that the government could not interfere with Indian worship ceremonies or despoil sacred sites. “It shall be the policy of the United States to protect and preserve for American Indians their inherent right of freedom to believe, express, and exercise the traditional religions.” The law declared clearly, for the first time, that Native Americans now merited the protections of the First Amendment.

The law passed in 1978, a mere 199 years after the First Amendment was ratified.