The Witnesses

A tiny, reviled, and obnoxious American religion forces the nation to define what religious liberty really means.

Excerpted from Sacred Liberty

Robert Fischer was trying to escape from Litchfield, Illinois, when the mob caught up with him. The crowd pulled him out of his car and started destroying his Jehovah’s Witnesses literature. It was June 16, 1940, war hysteria was mounting, and the residents were livid that Fischer and the other Witnesses refused, as a matter of conscience, to salute the American flag.

To demonstrate their love of flag, the crowd draped one over the front of the car—and slammed Fischer’s head against it, demanding that he kiss Old Glory. Fischer wouldn’t. Again, they smashed his head against the flag-covered hood. Again. Again. And again, for thirty minutes. The town’s chief of police sat nearby watching.

The attack was part of a wave of violence against Jehovah’s Witnesses that began in the 1930s. The Witnesses were a small group, just forty thou- sand people, quirky and original—exactly the sort of religious startup that the Madisonian free market allows. But their unusual theology and aggressive proselytizing prompted what Brigham Young would have called “mobocracy.” Witnesses were beaten, jailed, tarred and feathered, and, in one case, castrated. The response: an equally aggressive effort by the Jehovah’s Witnesses to use the American courts to protect their rights. At least thirty-seven religious freedom cases involving Jehovah’s Witnesses were argued in front of the United States Supreme Court. The decisions that were handed down changed the understandings of, and rules for, religious freedom. Because of their efforts, religious freedom was finally guaranteed at the state and local levels, as James Madison and John Bingham had hoped. “Seldom, if ever, in the past has one individual or group been able to shape . . . our vast body of constitutional law,” legal scholars John Mulder and Marvin Comisky wrote in 1942. “But it can happen, and it has happened, here. The group is Jehovah’s Witnesses.”

The Jehovah’s Witnesses’ emphasis on constitutional law turned out to be crucial because when a religious minority is small and unpopular, it will not be able to gain protection through political clout. It must gain strength from the idea of religious freedom—which can be actualized only through an independent judiciary. The Witnesses worked the courts, prompting federal judge Edward Waite to ask: “If ‘the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church,’ what is the debt of Constitutional Law to the militant persistency—or perhaps I should say devotion—of this strange group?”

“Worse than Traitors”

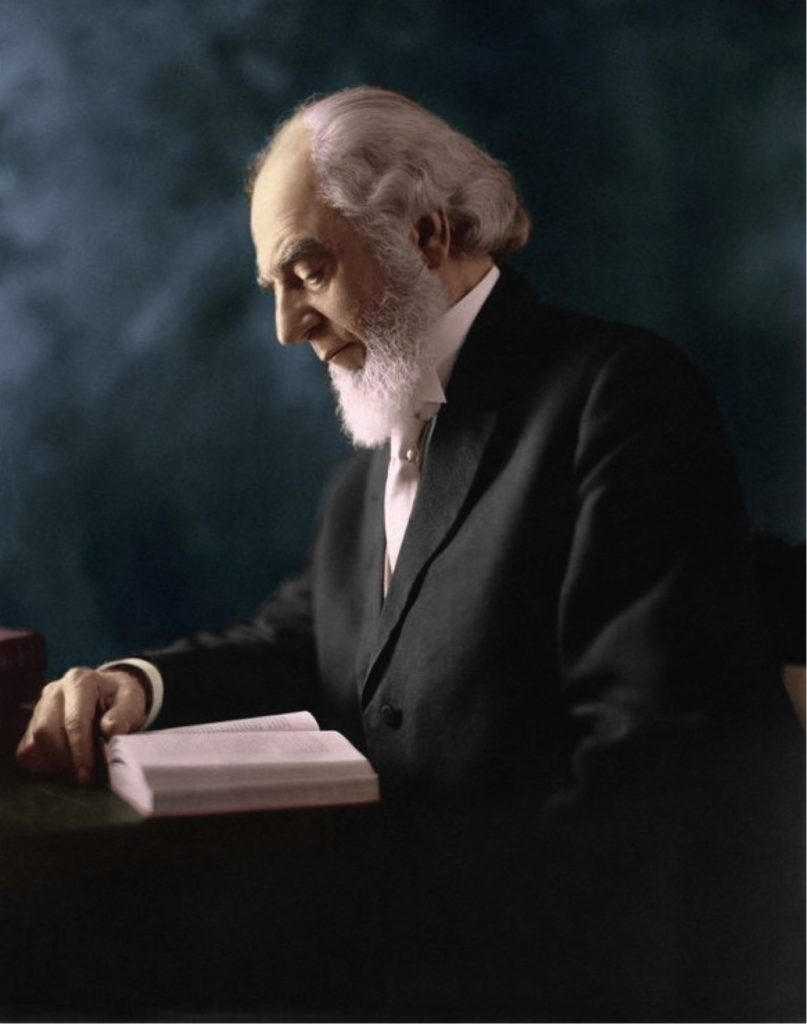

In 1869, seventeen-year-old Charles Taze Russell was working in his father’s clothing store in Allegheny, Pennsylvania. One Sunday, he heard an Adventist minister preach about the imminent return of Christ. Intrigued, he started a Bible study group. He published a pamphlet, The Object and Manner of Our Lord’s Return, and then other pamphlets and books. Russell initially described his project as more of a faith-based publishing operation than a new religion.

Over time, Russell developed his own theology of biblical literalism, which maintained that Christ would return to restore paradise on Earth, not destroy it. He laid out in great detail a schedule for Christ’s return and the specific steps his followers would need to take to gain salvation. By the time of his death in 1916, Russell’s books and tracts had sold 20 million copies.

Soon after Russell’s death, the controversial views of the International Bible Students Association (as the Witnesses were called back then) began to enrage the authorities. The government believed that the writings of Joseph Rutherford, who had taken over as head of the movement, would stir resistance to the World War I draft. They pointed to this passage in Russell’s Finished Mystery:

Nowhere in the New Testament is patriotism (a narrowly minded hatred of other peoples) encouraged. Everywhere and always murder in its every form is forbidden. And yet under the guise of patriotism civil governments of the earth demand of peace- loving men the sacrifice of themselves and their loved ones and the butchery of their fellows, and hail it as a duty demanded by the laws of heaven.

They were not traditional pacifists. The Bible passages that drove them were not so much Jesus’s teachings about nonviolence as apocalyptic writings about the ultimate battle between Jehovah and Satan. All governments, including that of the United States, were controlled by the devil, they believed. (The theological roots: Satan had taunted Jehovah by saying that no one would remain faithful if subject to the devil’s influences. Jehovah took the bet and allowed Satan to run the governments, and all religious institutions too, as a test.)

Though The Finished Mystery is a turgid, difficult-to-follow collection of Bible verses, exegeses, and excerpts from other writings, the US Department of Justice thought it could go viral. “The only effect of it is to lead soldiers to discredit our cause and to inspire a feeling at home of resistance to the draft,” stated a memorandum from the US attorney general. He was not convinced that the Bible Students were actually driven by religious views. “The International Bible Students Association pretends to the most religious motives, yet we have found that its headquarters have long been reported as the resort of German agents.”

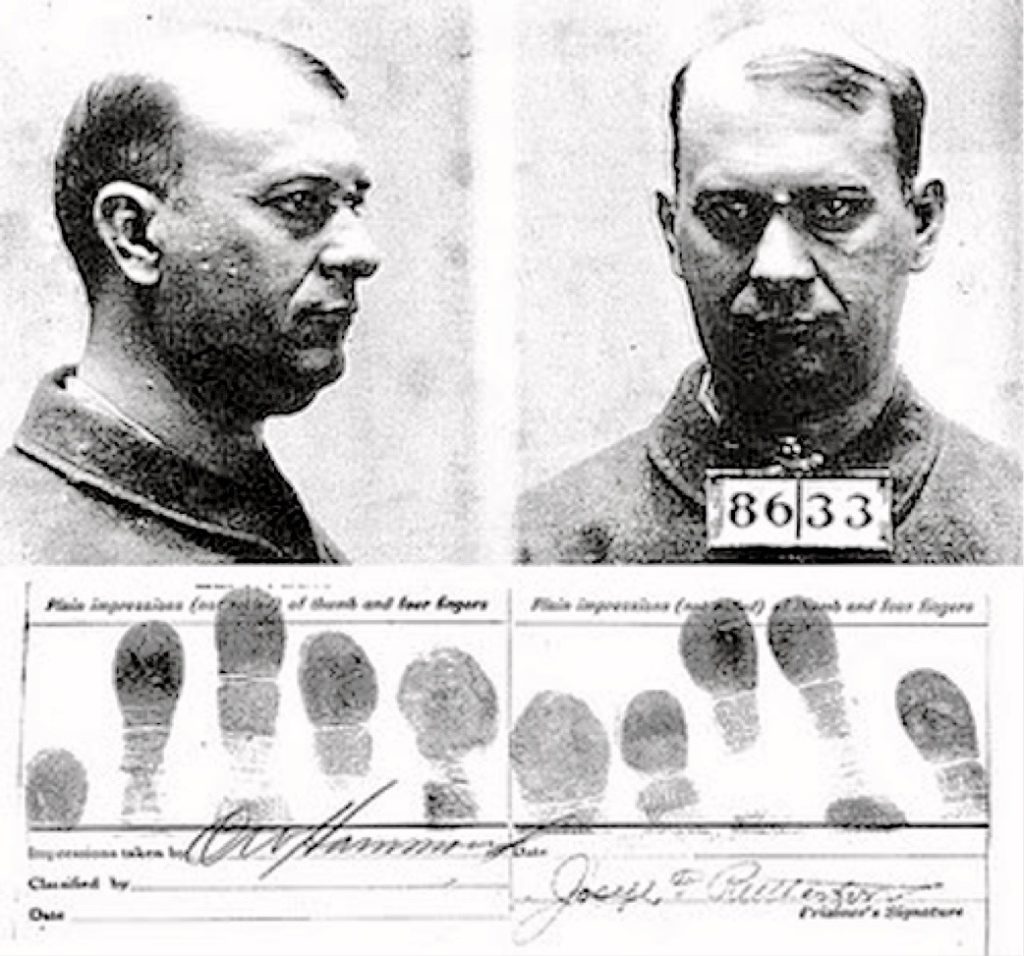

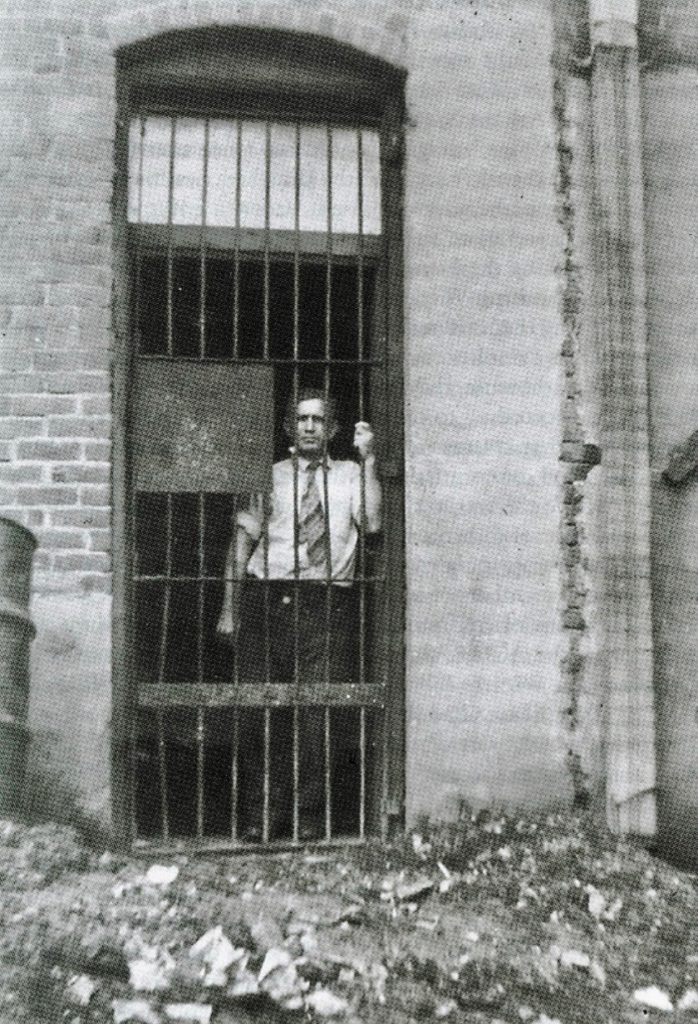

The US government indicted eight leaders under the Espionage Act of 1917 for “unlawfully and willfully conspiring to cause insubordination, disloyalty, and refusal of duty of the military.” Judge Harland B. Howe wrote that the Bible Students’ “religious propaganda” was “a greater danger than a division of the German Army.” The sincerity of their religious convictions made them potentially more persuasive. “They are worse than traitors,” he declared. “You can catch a traitor and know what he is about. But you cannot catch a man who does what they did under the guise of religion.” The leaders were convicted and sentenced to an astonish- ing twenty years in prison. Though the charges were later thrown out, Rutherford served nine months in a federal penitentiary.

For Rutherford, the experience was searing. It not only cemented his attitude toward government but also stoked his antagonism toward other religious groups, as many religious leaders had cheered the war, and some had even applauded the arrest of the Bible Students. The organization, renamed Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1931, poured out writings about the com- ing Armageddon and the sinister behavior of the Catholic Church. The Church was “the chief visible enemy of God, and therefore the greatest and worst public enemy,” declared Rutherford.

As World War II approached, the Witnesses’ beliefs about patriotism got them into trouble again—at first, with the Nazis. Jehovah’s Witnesses in Germany refused to say “Heil Hitler,” offer the salute of loyalty, or join the army. Hitler shut down the Witnesses’ printing presses and banned them outright. After the draft was instituted, thousands more were arrested for refusing to serve in the army. Some ten thousand Witnesses were sent to prisons and concentration camps, where they were identified with purple triangles. They were frequently tortured—and yet also offered their freedom if they signed an affidavit renouncing their faith. In one case, the Witnesses in a concentration camp were gathered together outside and forced to watch as one of their leaders was shot to death. The Nazis then handed out pieces of paper granting the other Witnesses their freedom if they denounced their religion. None did, and most likely they all died. In all, approximately two thousand Witnesses were killed by the Nazis. “The Jehovah’s Witnesses were literally the only martyrs of the Holocaust,” said Michael Berenbaum of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The Jews were victims because their experience was not a matter of choice. But the Witnesses did have a choice. They are people to be respected for not giving in.”

The Witnesses rankled American authorities too. States pushed to inculcate patriotism in schools, often by having children salute the flag. The Witnesses had two problems with the practice. Since governments were controlled by Satan, the law “that compels the child of God to salute the national flag compels that person to salute the Devil.” Satan was fond of the flag salute rules because it turned the flag into an object of worship, violating the first of the Ten Commandments (“Thou shalt have no other gods before me. Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image . . . thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them”).

The flag had become a new god, more important than Jehovah, they believed. Saluting it was no minor infraction. Witnesses were thought to have entered into a covenant with God, predicated on following the laws precisely. A Witness who broke faith would lose the possibility of everlasting life. Rutherford generously allowed that, of all the Satanic governments of the world, the United States was definitely the best—but he insisted that resistance to the flag salute was nonnegotiable. In a book called Children, Rutherford explained:

Satan influences public officials and others to compel little children to indulge in idolatrous practices by bowing down to some image or thing, such as saluting flags and hailing men, and which is in direct violation of God’s commandment (Exodus 20:1–5).

In 1935, Carleton Nichols, a brave third grader in Lynn, Massachusetts, stood quietly, hands at his side, during a flag ceremony. He explained that as a Jehovah’s Witness, he couldn’t honor “the Devil’s emblem.” After the school punished Nichols and his parents, Rutherford went on the radio to praise Carleton for “declaring himself for Jehovah God and his kingdom. . . . All who act wisely will do the same thing.” Rutherford noted that the American flag salute was awfully similar to the salute that Germans were giving Hitler. (At the time, the custom was to extend one stiff arm upward while reciting the pledge. In 1942, after the United States entered World War II, Congress amended the US Flag Code, stipulating that the right hand should be placed over the heart instead.)

Among those who heard Rutherford’s remarks was the family of Walter Gobitas of Minersville, Pennsylvania, a working-class coal-mining town. Lillian, a seventh grader, and Billy, a fifth grader, both decided to stop saluting the flag. Billy explained in a note, “I love my country and I love God more and I must obey his commandments.”

They were expelled. School superintendent Charles Roudabush believed that the patriotic rituals were crucial and the religious objections bogus. Those who abstained were “aliens.” The family, with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Witnesses’ main office, appealed the ruling. During the trial, Roudabush had this exchange with the district court:

roudabush: We feel it is not a religious exercise in any way and has nothing to do with anybody’s religion.

the court: Do you feel that these views to the contrary here held by these two pupils are not sincerely held?

roudabush: I feel that they were indoctrinated.

the court: Do you feel their parents’ views were not sincerely

held?

roudabush: I believe they are probably sincerely held, but misled; they are perverted views.

In 1940, in Minersville School District v. Gobitis, the US Supreme Court ruled 8–1 against the Witnesses.25 As it had sixty-one years before, in its ruling against the Mormons, the Court concluded that the First Amendment did not license behaviors that the local community finds destructive.

The next three years saw a massive increase in persecution of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Whether it was caused primarily by the Gobitis decision or by the Witnesses’ decision to start proselytizing on street corners (in addition to going house to house), the attacks on Witnesses became horrific.

In Lookout, West Virginia, Witnesses were brought to the mayor’s office, where they were roped together like cattle, at two-foot intervals, and forced to drink castor oil. In the midst of the attack, liquored-up American Legion members, with no sense of irony, declared that their purpose was to “promote peace and good will on earth.”

In Nebraska, two men appeared at the home of Witness Albert Walkenhorst. They claimed to be coreligionists and asked him outside to discuss the Bible. Then they grabbed him, brought him to a grove of trees, and castrated him. “There, that will hold you for a while,” one of them joked.

In Little Rock, Arkansas, a group “armed with guns, pipes and screw- drivers . . . mercilessly beat all the Witnesses they could find,” according to a report by the ACLU.

In Connersville, Indiana, several middle-aged female Witnesses were charged with flag desecration because they had given out literature op- posing the flag salute requirement. Two pleaded not guilty and were sentenced to two to ten years in prison. Their attorney was beaten and run out of town.

In Flagstaff, Arizona, a Witness reported that residents asked him if he would salute the flag.

When I replied that I respected the flag but was consecrated to do God’s will and did not salute or attribute salvation to the flag they cried, “Nazi spy!” knocked me down, beat me badly, and finally knocked me out—then dragged and pushed me across the street to a service station and again tried to make me salute the flag. I was dizzy, befuddled and don’t clearly remember anything further except that a considerable crowd had gathered yelling “Nazi spy!— Heil Hitler!—String him up!—Chop his head off!”

Witnesses’ businesses were boycotted. In Belleville, Illinois, they were kicked off relief rolls. In Clarksburg, West Virginia, local unions forced the firing of seven Jehovah’s Witness glass cutters. Often, the attacks were led by members of the American Legion, with the active support or at least acquiescence of local law enforcement. The Witnesses got little help from the press (“44,000 Americans Join Freak Cult That Hates Everything!” blared the Chicago Daily Tribune).

The scale of the harassment and persecution grew and grew. From 1933 to 1951, there were 18,866 arrests of Witnesses. From 1940 to 1943, 843 instances of persecution were reported to the US Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, according to an analysis by historian David Manwaring. The ACLU estimated that more than two thousand students had been ejected from school by 1943. In many cases, families put the kids in Kingdom Schools after they were expelled—and were then prosecuted for truancy. In Monessen, Pennsylvania, Witnesses set up a Kingdom School to accommodate those who had been kicked out of local schools, but the mayor viewed it as communistic, padlocked the school, and seized literature. When 146 Witnesses went to Monessen to protest, the mayor put them all in jail overnight.

Just as the Mormon claims were mocked as being not genuinely religiously grounded, many found it hard to believe that the Witnesses’ refusal to salute the flag was truly a matter of conscience. “To symbolize the Flag as a graven image and to ascribe to the act of saluting it a species of idolatry,” the Florida Supreme Court declared, “is too vague and far- fetched to be even tinctured with the flavor of reason.”

But the Witnesses continued to resist the flag salute law and proselytize on the streets. The reason is important. While Russell had believed that only 144,000 people would be saved, making it pointless to exert much energy converting people, Rutherford had amended the theology. There was a second class of people, the Jonadabs, who would live in the new Edenic paradise that Jesus would be leading. But only those who had become Witnesses by the time of Jesus’s arrival—which was any day now—would be saved, so time was of the essence.

They also passionately believed that the courts could help. By 1933, the organization’s leadership had pledged to appeal all unfavorable ruling and provide lawyers to carry forward the cases. That may have been partly because their leader, “Judge Rutherford,” was an attorney. At Witness conventions, the organization offered special training in legal procedures. They distributed a pamphlet, the Order of the Trial, to help Witnesses defend themselves in court. The ACLU, which helped bring many of the cases, also offered rewards in communities for information leading to the prosecution of anti-Witness assailants. Rutherford’s faith in the legal system was not groundless; Witnesses won more than one hundred decisions from state supreme courts.

Breakthrough

Newton Cantwell and his son Jesse went to spread the gospel in a Catholic neighborhood in New Haven, Connecticut. They brought a portable hand-cranked phonograph and played bits of Rutherford’s book Enemies, which includes passages such as “The Roman Catholic hierarchy is a selfish and devilish organization, operating under the misleading title of ‘Christian religion,’ and desperately attempting to gain control over all the people of the earth.” This enraged local residents, and the sheriff arrested the Cantwells and charged them with violating a Connecticut law forbidding the soliciting of funds without a license. Under the law, the secretary of the local public welfare council got to determine whether an organization was a bona fide religion. Like the Baptists in the 1700s, the Witnesses did not believe in government certification and thus refused to seek such permits.

The Witnesses wanted to challenge the law, but there was an obvious problem with the case: the violation of their religious liberties in this case was being perpetrated by a local government. The compromise forged by James Madison around the First Amendment meant it would apply (much to his disappointment) only to actions by the federal government. Although John Bingham had intended the Fourteenth Amendment to repair that flaw, for eighty years the courts had refused to do so. But the Witnesses’ lead attorney, Hayden Covington, knew that the Supreme Court had already taken a big step toward what would become known as “incorporation”—the idea that the Fourteenth Amendment had applied the Bill of Rights to the states and not just the federal government. In Gitlow v. New York in 1925, the Court had ruled that the First Amendment protected freedom of speech on the state and local levels because of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court then incorporated freedom of assembly in 1937. Covington wondered: could freedom of religion be next?

In 1940, in Cantwell v. State of Connecticut, the Supreme Court unani- mously ruled for the Jehovah’s Witnesses, declaring that, thanks to the Fourteenth Amendment, the “free exercise of religion” was indeed guar- anteed to all. No longer could local governments trample religious free- dom rights without the Bill of Rights having something to say about it.

There it was. Madison had failed to apply the principle of religious free- dom to the states, but thanks to the Civil War, the Radical Republicans, John Bingham, the United States Supreme Court, and finally the Jehovah’s Witnesses, religious liberty was now an inextricable part of the national creed, enforceable in every jurisdiction.

In taking this historic step, the Court said that while religious freedom was not an unlimited right, the state must not “unduly” infringe on it. States could regulate only when there was a “clear and present danger of riot, disorder, interferences with traffic upon the public streets, or other immediate threat to public safety, peace, or order.” The Court would spend the next seventy-five years assessing when religious liberty went too far. But from that day forward, all religious freedom questions—even local matters—were potentially matters for the federal courts to decide, governed by the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

Madison would have been particularly tickled by the Court’s grappling with the diversity of viewpoints in America. In Cantwell, the Court acknowledged how messy religious competition could be. “In the realm of religious faith, and in that of political belief, sharp differences arise,” Justice Owen Roberts noted. “In both fields, the tenets of one man may seem the rankest error to his neighbor.” Yet even when religious views are deemed strange or even harmful, they must be given wide berth. Under the “shield” of religious freedom, Roberts wrote, “belief can develop un- molested and unobstructed.” Acknowledging the centrality of this concept in a pluralistic society, he concluded, “Nowhere is this shield more necessary than in our own country, for a people composed of many races and of many creeds.”

A year later, the United States entered World War II. As the American Legion unleashed a national campaign “to foster and perpetuate a one hundred percent Americanism,” cities, states, and school boards around the country stepped up their efforts to encourage patriotism in part by having schoolchildren pledge allegiance to the flag. Emboldened by Cantwell, the Witnesses decided to again challenge the flag salute laws.

In a way, the Witnesses’ efforts to strike down flag salute laws were more audacious than their efforts to protect their proselytizing work in the streets. Decreeing that a religion can’t hand out its tracts is a clear restriction of its “free exercise.” But flag salute laws were a bit different. They did not target Jehovah’s Witnesses or stop them from expressing themselves. The statutes had a secular goal, encouraging patriotism.

But a few things had changed since the last flag salute case, Gobitis, was decided against the Jehovah’s Witnesses. One was the Cantwell ruling, which had opened up local school boards to the scrutiny of federal courts when it came to religious questions. Just as important, the reaction to Gobitis had been negative. The New Republic had mocked the Court for “heroically saving America from a couple of schoolchildren whose devotion to Jehovah would have been compromised by a salute to the flag.” Legal experts were also aware of the wave of persecution that had followed it and the courageous sincerity of the victims.

The Witnesses’ lead attorney, Hayden Covington, found his test case near Charleston, West Virginia. In 1942, the state board of education had issued a rule requiring kids to salute the American flag—“in the spirit of Americanism”—and declared that refusal “would be regarded as an Act of insubordination.” Ten-year-old Marie and eight-year-old Gathie Barnett, the children of a pipe fitting helper at a local DuPont factory, refused to salute during a ceremony at Slip Hill Grade School. They were expelled. The Witnesses appealed all the way to the highest court.

In his brief to the US Supreme Court, Covington compared the Gobitis decision to Dred Scott v. Sandford as a case that would live in infamy. He argued that freedom of speech—which had been gaining greater protection from the Court—must include the freedom not to speak.

In West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, the Court in 1943 sided with the Witnesses, overturning the Gobitis decision of just three years earlier. Three of the justices who had voted against the Witnesses switched sides.48 Justice Robert H. Jackson noted that, because of the Four- teenth Amendment, the Supreme Court had not only a right but an obli- gation to intervene on a local level because the “small and local authority may feel less sense of responsibility to the Constitution.”

Surprisingly, Jackson objected to the flag salute requirement not so much because it forced religious beliefs on Jehovah’s Witnesses, but be- cause it forced beliefs in general on anyone. “Those who begin coercive elimination of dissent soon find themselves exterminating dissenters,” wrote Jackson, the specter of European Fascism evident between the lines. “Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.” In one of the most famous sentences from a Supreme Court decision, he declared, “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.”

This was an important moment for religious liberty—and it would create scores of new dilemmas for the United States in the years that followed. With Barnette and other cases of that era, the Court gave more power and deference to religious believers. From then on, even if a law wasn’t intended to hurt a religion, it might still be viewed as unconstitutional if the harm it inflicted was significant or if the law’s secular purpose wasn’t important enough. The devil, as it were, was in defining “enough”: what secular purpose could be so important that it justified inflicting collateral damage on a religion? What if religious groups felt that taxation infringed upon their rights? Or what if they believed that teaching evolution in schools violated their religious beliefs? How far should we go to accommodate religious Americans?

In his dissent, Justice Felix Frankfurter prophesied that this new world would be fraught with constitutional danger. The justice, a Jew, began with an unusually personal bit of credibility building: “One who belongs to the most vilified and persecuted minority in history is not likely to be insensible to the freedoms guaranteed by our Constitution.” Nonetheless, he said, religious minorities could end up with too many “new privileges.”

[The First Amendment] gave religious equality, not civil immunity. Otherwise, each individual could set up his own censor against obedience to laws conscientiously deemed for the public good.

Noting that there were 250 distinctive religious denominations in the United States, he wondered whether the Court would now have to assess the sincerity or significance of each of their beliefs. After all, if a belief is a minor part of a theology, perhaps the government should be less worried about infringing upon it. Frankfurter’s dissent unearthed a great irony: the Court’s desire to protect religion from the state could force it to become more involved in sensitive judgments about religious claims. Frankfurter’s Barnette predictions proved prescient. The Court was entering a new era in which society would be increasingly sensitive to the rights of religious groups and, as a result, drawn into difficult balancing acts. The Court took the right path, but that didn’t mean it would be smooth.

From 1940 to 1944, the US Supreme Court heard a variety of religious freedom cases, many involving the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Case by case, the Court sketched out new principles, sometimes ruling against the Witnesses but more often in their favor. Yes, the Witnesses (and other people of faith) could proselytize without having to get a permit. Yes, they could do so even if it was in a company town. No, they couldn’t have eight- year-olds do it in violation of child labor laws. Yes, they could do it with- out paying a tax. No, they could not hold a parade in which marchers carried signs reading “Religion Is a Snare and a Racket” without obtaining a license. No, they could not tell the local marshal that he was “a damn fascist and a racketeer.” No, they could not avoid both military and civilian service (and some 4,300 Witnesses were jailed for their refusal). And yes, they could hold worship services in the park. Gradually, this despised religion won expanded rights for all believers.

Why was it that the Jehovah’s Witnesses ended up playing such a critical role in the expansion of religious liberty? As with the Mormons, the Witnesses’ obnoxiousness made all the difference. Because their own salvation depended on their success at saving others, they were famously pushy. Because their theology required them to tell “the truth” about not only their own faith but others’ (i.e., the harlots, dupes, and pawns of Satan), they excelled at provoking overreactions. Because they were biblical literalists and millennialists, they adopted extraordinarily unpopular positions, such as being avowedly unpatriotic in the midst of both world wars. Because they were religiously intolerant, they alienated potential allies among other religions. Alone and unpopular, they could not influence legislatures. But because they were litigious, they forced the courts to probe the real meaning of the First Amendment. Because they published their controversial views—and then spread them on street corners—they were able to gain additional protection from the First Amendment’s guarantees of freedom of press, speech, and assembly.

In a way, the rise and role of this ornery faith fit the Madisonian model perfectly. It was a religious startup—invented by a seventeen-year-old possessed with the belief that he’d found a better way. This grew into a movement of ordinary Americans who challenged those in power, won, and brought expanded rights for everyone. But their path to success was different from that of the Catholics and Mormons, who gained acceptance in part through their numerical clout. The Witnesses did not have that option. They needed to rely on the law, for, in the words of Justice Jackson, “the very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities.” It turned out that the Madisonian model could not rely only on a multiplicity of sects; it also had to make that “parchment barrier”—the declaration of rights—become a powerful force. For that to happen, the nation needed an assertive, independent judiciary.

As a legal matter, the Jehovah’s Witnesses cases triggered two seismic shifts. First, the Constitution now protected Americans from the tyranny of state and local governments (as Madison and Bingham had wanted). Second, America would from then on have to seek ways to accommodate the sensitivities of religious believers in those gray areas where secular laws inadvertently infringe upon religious convictions. It was no longer enough to not persecute a group—America would have to bend over backward to give religions room to breathe. This new era of accommodation has drawn the courts and legislatures into many more religious controversies but in the service of a more expansive notion of liberty.

Over time, the Jehovah’s Witnesses became less aggressive and insulting, which is part of the reason that there are more than 8 million of them around the world today. Undoubtedly, they’ve benefited from sanding off their rough edges. But fortunately the Witnesses in the 1940s were still plenty abrasive.