Martyrs of Religious Freedom in America

Thousands of Americans protested for religious freedom — and some gave their lives. Here are a few that we know about. These descriptions are excerpted from Sacred Liberty

Mary Dyer

By modern standards, Dyer was no groovy freethinker. Like many of the other Puritans who came to America seeking religious sustenance, she was a serious Bible-following Christian (how else to explain her naming her son Mahershalalhashbaz, after a line in Isaiah 8:1?). But at twenty-five, she fell in with a troublesome crowd in Boston. She attended meetings at Anne Hutchinson’s house, where the women had the audacity to critique the weekly sermons of the local minister, accusing him of favoring the heretical doctrine of salvation by works. By 1636, Hutchinson and Dyer had been marked by the Puritan elders as dangerous radicals.

The local leaders believed they had another clear piece of evidence that Dyer was in the devil’s orbit: she gave birth to a horribly deformed stillborn baby. When officials heard the news, they had the baby exhumed so they could catalog its features. (“It had no forehead, but over the eyes four horns, hard and sharp … all over the breast and back full of sharp pricks and scales.… It had on each foot three claws, like a young fowl, with sharp talons.”) A history book from that time concluded that the “Lord had pointed directly to their sinne” by having Mary Dyer bring forth “a very fearfull Monster.”[

Alas, this was just the first chapter in the remarkable story of Mary Dyer, one of the first great American religious martyrs. Several years later, she met George Fox, founder of the Society of Friends, or the Quakers. She was drawn to the Quaker teaching that one could find the light of God within oneself and (therefore) need not rely on clergy or prescribed ritual.

In Massachusetts, being a Quaker was not just frowned upon—it was illegal. The punishment was whipping on the first offense, having an ear cut off after the second, and execution on the third. The authorities enforced the law with sadistic enthusiasm. One elderly Quaker, William Brend, was whipped 117 times with rope “so that his flesh was beaten black and as into a jelly, and under his arms the bruised flesh and blood hung down.”[

The first time Dyer returned to Massachusetts, in the fall of 1657, she was arrested and expelled. A few years later she returned to Boston to declare solidarity with two imprisoned Quaker friends, William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson, and to challenge the system—or, as she put it, to “try the bloody law.” For this act of civil disobedience, she was sentenced to death.

Governor John Endecott puzzled over the persistence of Dyer and her friends. “We have made many laws and endeavored in several ways to keep you from among us, but neither whipping nor imprisonment, nor cutting off ears, nor banishment upon pain of death, will keep you from among us,” he declared.[

On October 27, 1659, the three were brought to the Boston Common to be hanged. The colonial masters performed the executions sequentially rather than simultaneously, so Dyer could watch as her friends’ necks snapped.

Suddenly, someone in the crowd yelled, “Stop, for she is reprieved!” This was no act of last-minute mercy. The whole drama had been orchestrated by the Massachusetts court so Dyer would witness the deaths as a lesson and then be freed. She left the area for a time, but on May 21, 1660, she was spotted walking the streets of Boston and was again sentenced to death. On June 1, wearing a plain gray dress, cloak, and bonnet, she walked from the prison to the Boston Common. A row of drummers played to drown out any words of encouragement that might be offered her or that she might speak to the crowd. When the commander of the military declared that she had brought this on herself by defying the law, she responded, “I came to keep blood-guiltiness from you, desiring you to repeal the unrighteous and unjust law.”[

A rope was tied to a large elm tree and a ladder propped against it. After she climbed it, the noose was placed around her neck and her arms and feet were bound together. The ladder was removed, and Mary Dyer was executed by the Holy Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the crime of attempting to practice her faith.

Joseph Smith

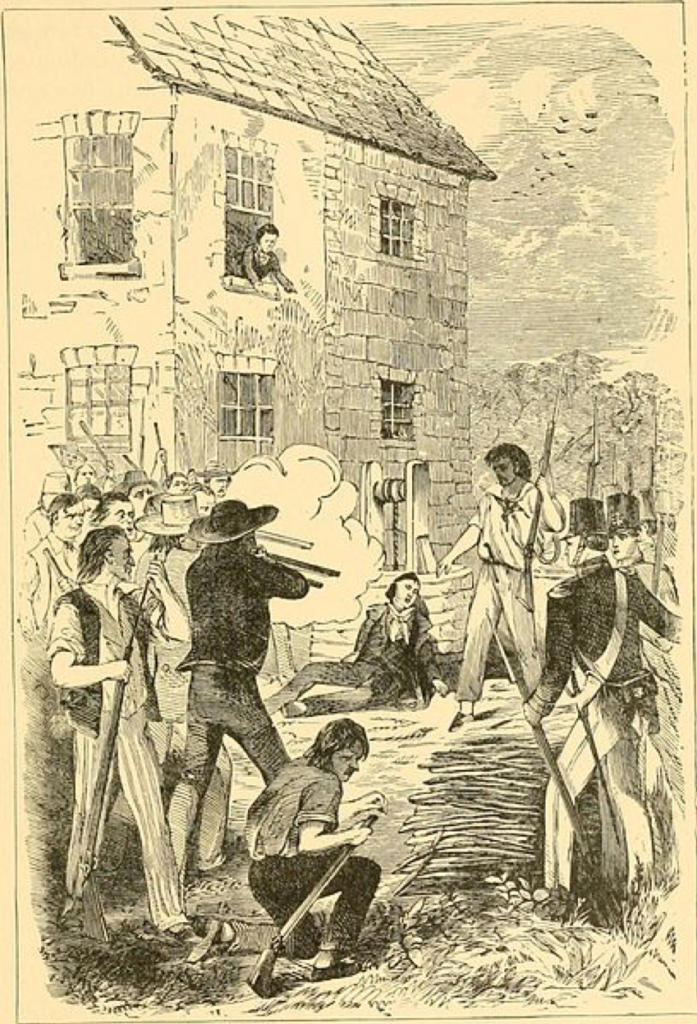

In 1844, residents of Carthage, Illinois passed a formal resolution in 1844 stating that if “the prophet and his miscreant adherents” did not surrender, “a war of extermination should be waged to the entire destruction, if necessary for our protection, of his adherents.” They kept their word. As Smith sat in Carthage’s jail on June 27, 1844, about 125 men emerged single file from the woods. Several broke down the door and shot Smith’s brother Hyrum in the face. As Joseph Smith scrambled away, they shot him in the back, causing him to fall out of a nearby window. He landed on the ground in front of a crowd of bayonet-wielding militiamen whose faces were smeared with mud. Seeing that he was still alive, one of them propped him up against a wall. His colleagues then fired several more rounds into his chest.[

Sardius Smith & The Families of Hauns Mill

In the fall of 1838, Lilburn Boggs, now governor, was told—falsely—that Mormons had massacred a group of Missouri militia members. He soon issued one of the most infamous documents in the history of religious liberty: Missouri Executive Order 44. Writing to his military commander, General John B. Clark, on October 27, Boggs declared that Mormons had adopted “the attitude of an open and avowed defiance of the laws, and of having made war upon the people of this State.” Therefore, he wrote, the Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary for the public peace.[

To implement what came to be known as the “extermination order,” the general was instructed to increase his forces “to any extent you may consider necessary.”

Three days after the order was issued, on October 30, 1838, the biggest religiously motivated massacre in American history occurred. About two hundred fifty Missourians, including a state senator, arrived at Haun’s Mill, a small Mormon community. They rode their horses forward, assembled in a line, and, when they were about seventy-five yards away, opened fire. Children and women screamed and ran for cover.[ Some retreated to the blacksmith shop, built of loose-fitting logs. After raining bullets on it for a while, the militia members entered the building. A nine-year-old boy, Sardius Smith, was still alive, having crawled under the bellows for protection. He pleaded for his life. One soldier put his gun to the boy’s head and, according to an eyewitness, “literally blew off the upper part of it, leaving the skull empty and dry while the brains and hair of the murdered boy were scattered around and on the walls.” When one of the other militia men suggested that his actions were excessive, the gunman replied, “Nits make lice.”

The attackers chased down a white-haired seventy-eight-year-old Mormon, Thomas McBride, who had fought under Horatio Gates and George Washington in the Revolutionary War. They demanded his gun, which he gave them. They then took a corn knife, a scythe used for cutting stalks, and chopped up McBride’s face. The soldiers stripped the dead of their boots and clothing and told the survivors that if they didn’t leave by the next day, they too would die. In all, seventeen Mormons were killed and fifteen wounded. Fearful that the soldiers would desecrate the bodies, the survivors quickly dumped them in an unfinished well. “All through the night we heard the groans of the dying,” one recalled.[

The Philadelphia Bible Riots

When Pennsylvania created its public school system in 1834, the legislature required that it use the Bible to teach morality. By “Bible,” it meant the King James Version. The problem was that, for several hundred years, Catholics had rejected the King James Version in favor of the Douay-Rheims Version. Catholics also used a different version of the Ten Commandments. For Protestants, the third Commandment was “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above.” Catholics had a long tradition of creating literal depictions of Jesus on the cross and icons of the saints.

Philadelphia’s Catholic bishop, Francis Kenrick, objected. Born in Dublin, he had immigrated in 1821 after receiving his doctorate, and he now managed a fast-growing diocese. “the reading of the protestant version of the bible is unlawful and no catholic parent can permit his children to use it as a schoolbook or otherwise,” he wrote in the Catholic Herald in 1841. The rule violated “the rights of conscience,” which were supposed to be “inviolable.” Many Catholic parents instructed their children to refuse to read the “mutilated work,” as they called the King James Version.[

Kenrick suggested that schools continue to use the Protestant Bible but that Catholic students be allowed to read from the Catholic Bible and be excused from singing Protestant hymns. He did not propose that the Bible be removed from the schools or that Protestant children be kept from reading the King James Version.

The members of the Board of Controllers, which managed the school system, were mostly Protestants, but they knew that the Catholic population had risen from 21 percent in 1808 to 39 percent in 1832. So they crafted what they thought was a Solomonic compromise. Catholic students should not be forced to read a Bible to which they were “conscientiously opposed.” But while they could bring in a Bible of their own, it had to be one “without note or comment,” which ruled out the Catholic Bible. Their Liberty of Conscience resolution,[vi] as they called it, angered everyone. Protestant leaders thought the board had capitulated to evil, falsely asserting that the Catholics wanted to exclude the Bible from the schools. The Catholics were perfectly free to leave the common schools if they didn’t like them, they argued. “Protestants founded these schools, and they have always been in a majority,” explained an article in the Presbyterian. “Why then should the minority who have come in afterwards for the benefits of these schools” get to change the rules? The Protestant Banner warned that acceding to the Catholic position would mean, in effect, “erecting the cross of the antichrist over our common school houses.”[

Philadelphia’s Protestants organized, with more than eighty ministers of various Protestant denominations setting aside their own differences in 1842 to form the American Protestant Association. They maintained that “Romanism … under a foreign priesthood” was aggressively trying “to destroy the religious character and influence of public Protestant education.” The American Republican Association, a nativist group, urged that naturalized citizens—those not born in the United States—be excluded from public office.

The next year, a teacher in the Kensington district falsely claimed that her principal had told her to stop teaching from the Bible. A school official then told an audience at a Methodist church that the principal, who was Catholic, was acting under “Popish dictations” and that it was time to “resist such attempts ‘to kick the bible from the Public Schools.’” The Episcopal Recorder asked:

Are we to yield our personal liberty, our inherited rights, our very Bibles, the special, blessed gift of God to our country, to the will, the ignorance or the wickedness of these hordes of foreigners, subjects of a foreign despot.…?[

On March 4, 1844, a crowd of more than six thousand gathered across from Independence Hall to “save the Bible.” In response to the agitation, Kenrick hardened his line. While before he’d asked that Catholic students be excused from reading from the King James Version, he now asked that they be allowed to recite from the Douay-Rheims Version. And if that wasn’t possible, the schools should just avoid Bible readings altogether.[

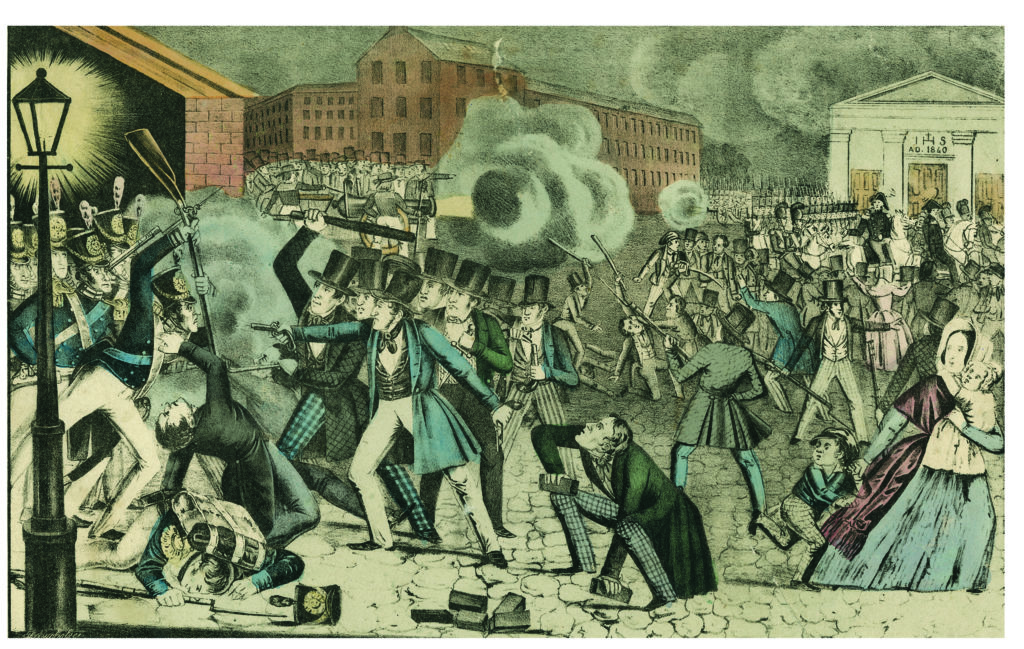

Tensions reached a dangerous level. On May 3, a Protestant group tried to hold a protest meeting in the Catholic area of Kensington, but club-wielding Irish Catholics drove them out. Three days later, more than two thousand Protestants returned. Fists flew, a scuffle broke out at a nearby market, a shot was fired, and an eighteen-year-old Protestant boy named George Shiffler was killed. The nativist press demanded revenge. “We write at this moment with our garments stained and sprinkled with the blood of victims to Native American rights—the rights of conscience,” the Daily Sun declared. Allowing Catholics to read their own Bible amounted to an assault on Protestant freedoms, the Native American declared. It was time “to arm,” since “the bloody hand of the Pope has stretched itself forth to our destruction.”[

In the ensuing riot, lasting from May 6 to May 8, about thirty Catholic homes were burned down. Some Protestants took a page from Exodus and adorned the doors of their homes with signs saying “native American” to ensure that the rioters passed them over. The Sisters of Charity convent was destroyed, as was St. Augustine’s Church, including its library of five thousand books. The crowd gave a great cheer when the cross atop St. Augustine’s fell to the ground.

Hundreds of Catholic families loaded their possessions into wagons and fled to safety. The governor sent in thousands of soldiers to guard the churches and restore order. After a few months of calm, nativists organized a major show of strength during a July 4 parade. A float depicting an open Bible traveled the route. One banner read, “Our Fathers gave us the Bible—we will not yield it to a Foreign hand.” Another depicted an American eagle grasping the good book in its claws. The next day, it was discovered that, with the permission of the government, muskets were being stored in the basement of the St. Philip Neri Catholic Church. A nativist mob descended upon the church to demand the removal of the weapons and exchanged gunfire with the local militia. In all, between the May and July riots, about thirty people were killed.

The Victims of Wounded Knee

In 1883, the commissioner of Indian affairs, Hiram Price, issued what amounted to a full-scale attack on Native American religion. First, the government banned a variety of Indian dances, including the Sun Dance, the Scalp Dance, the War Dance, and “all other so-called feasts assimilating thereto.” Those guilty of the crime of unlawful dancing would lose rations for ten days. On the second offense, they could lose rations for thirty days. The third time, they could go to prison for ten to thirty days.[

Though dances varied by tribe, they were invariably an important part of their spiritual practice, a way of deploying the spirits for essential purposes and creating tribal cohesion. The Sun Dance, for instance, was used to summon spiritual help for those going on hunts or into battle or to beseech the Great Spirit for a good harvest. The preparation involved fasts, property giveaways, songs, and other elements over several days. Its most controversial feature was self-torture. The dancers sometimes cut themselves, and in some tribes the practice became gruesome—slits were cut into the skin, and straps were passed through them. The pain and loss of blood made it more likely that they would have visions. The government banned the dance, which had a particularly demoralizing effect on the Sioux, according to historian Robert Utley.

No longer could they appeal directly to Wi [the Sun] for personal power and assistance. No longer could they experience the pervading sense of religious security that came only from the Sun Dance.… The Sioux had been dealt a shattering emotional blow, and their lives began to seem like a great void.[

Throughout America, police were told to break up the dances. In 1885, James McLaughlin, the agent at Standing Rock Indian Reservation in modern-day North Dakota and South Dakota, proudly reported: “Three years ago the ‘tom-tom’ (drum) was in constant use, and the sun dance, scalp dance, buffalo dance, kiss dance, and grass dance, together with a number of feast and spirit dances, were practiced with all their barbaric grandeur; but all these are now ‘things of the past.’”[

The most catastrophic conflict arose over a newly created ritual called the Ghost Dance. It was promoted in the 1890s by a Northern Paiute prophet named Wovoka, who in 1889 reported that he had died and traveled to heaven, where God taught him a new dance and gave him a set of messages. If the Indians led good, honest, peaceful lives, he said, the dead would come back to life and the land would once again be full of buffalo and game. Illness and death would be banished. And then there was the part that drew special attention from the non-Indian population: if the dances were performed properly, a great cataclysm, perhaps a flood or an earthquake, would wipe out the whites. His message was similar to the millennial promise of Mormons, evangelical Christians, and many other faiths that look forward to the End of Days and the advent of a new Kingdom of God—with two differences: a dance would trigger the arrival of paradise, and white Christians would have no place in it. By one account, Wovoka believed that God’s vision would not spare the Indians’ tormentors. “When Old Man [God] comes this way, then all the Indians go to mountains, high up away from whites. Whites can’t hurt Indians then. Then while Indians way up high, big flood comes like water and all white people die, get drowned. After that, water go away and then nobody but Indians everywhere and game all kinds thick.”[

He told his followers to dance for four consecutive nights and then repeat this six weeks later. The ritual was preceded by a purification fast or sweat lodge ceremony. The dancers wore special shirts—the yoke was sky-blue, and the rest was decorated with images of the moon, stars, eagles, crows, and buffalo. These “ghost shirts” were said to repel bullets. They danced in a circle, hand in hand, gradually increasing the pace. As they glided around, dancers called out the names of their dead relatives, throwing dirt in their hair to signify grief. Excitement grew, and those who left the circle, said historian Rani-Henri Andersson, “fell to the ground with trembling limbs and lay motionless, seemingly dead.”[

Leaders from the Sioux, Shoshone, Arapaho, Cheyenne, and other tribes across the country traveled by train to present-day Nevada to size up Wovoka. Each recounted the meetings differently. Sometimes Wovoka was described as a prophet. At other times, he was Christ returned. In another account, Jesus was an Indian who had been driven from Earth by immoral whites. “God blamed the whites for his crucifixion,” the story went, “and sent his son Wovoka back to the Indians, since the whites were bad.”[

Word of Wovoka and the dance spread from tribe to tribe, aided by the telegram and the railroad. By 1890, at least thirty tribes participated, and it had become a most unusual phenomenon: a pan-Indian ceremony.

Remarkably, most accounts of Wovoka contained strong Christian elements. Several witnesses reported seeing wounds in Wovoka’s palms. Fast Thunder, a Christian who performed the Ghost Dance, recounted:

As I looked upon his fair countenance, I wept, for there were nail prints in his hands and feet, where the cruel white men had fastened him to a large cross. There was a small wound in his side also, but as he kept his side covered with a beautiful blanket of feathers, this wound could only be seen when he shifted his blanket.[

Rather than viewing the Christian elements as a sign that their theology was penetrating Indian consciousness and declaring victory, the missionaries saw the telltale signs of Satan. The devil, explained one missionary, had cleverly made a beguiling “combination of the old heathen dance and the idea of a Messiah brought in by a gleam of Christianity.”[ After visiting one of the dance camps at White River, Father Florentine Digman reported that there was no uprising afoot but that the Indians were enraged that the agents had threatened to cut off their rations if they kept dancing.

“Obey [the] order then and quit dancing,” the priest advised. “Why after all are you bent on dancing?”

“This is our way of worshipping the Great Spirit,” responded one of the Indian leaders.

“I fear it is another spirit that leads you astray.”

The Indian pointed out that the Christian missionaries couldn’t even agree with each other over the right way to pray. “Let us alone then, and let us worship the Great Spirit in our own way.”[

Government agents were less sanguine; they feared that the Ghost Dances would lead to violence. It’s important to understand the context. The Indians, especially the Sioux Indians in the Plains states, were in dire straits. The government had recently taken a big chunk of land to give to white settlers and the railroads, cutting their reservation in half. The Indians had so little land that they could no longer base their economy on hunting. The property they had left was difficult to farm, and 1890 saw a horrible drought. “The Indians were brought face to face with starvation,” wrote James Mooney, a government official who surveyed the area.[ The government’s response: to increase the Indians’ incentives to farm, they cut their rations.

Press coverage mostly made matters worse, suggesting or asserting, with no evidence, that the Ghost Dances were a part of Indian war preparations. By mid-December there were seventeen correspondents in the area. The Washington Post and Chicago Tribune quoted a military source who said that the “incantations and religious orgies” would soon lead to trouble. The New York Times ran an article with the headline “How the Indians Work Themselves Up to a Fighting Pitch,” which explained, “The spectacle was as ghastly as it could be: it showed the Sioux to be insanely religious.” A Washington Post piece blamed the whole thing on the Mormons. Relying on military sources, the press accounts tended to exaggerate the number of potential warriors, printing estimates of fifteen thousand to twenty-seven thousand when the number was probably more like five thousand. More to the point, extensive historical research has found that the dancers were not planning an uprising.[ Settlers became alarmed and started leaving the area.

The news accounts also reflected the view that the real driver of the dancing was Sitting Bull, the renowned leader then living at Pine Ridge. That wasn’t true. Sitting Bull had heard of the dancing late in the game and was reportedly ambivalent about it. But as the man who had defeated Custer, Sitting Bull—still an ardent opponent of the whites—was the most frightening Native American alive, and he was an easy villain for reporters intent on hyping a dramatic showdown. Royer pushed that line too and demanded that Sitting Bull be arrested.

In Washington, President Benjamin Harrison was weighing political as well as military factors. Harrison and the Republicans, argues historian Heather Cox Richardson, figured that taking military action would convince the white settlers that the government had their back. The president told the secretary of war to intervene.

On December 15, a group of Indian policemen at Standing Rock Indian Reservation moved to arrest Sitting Bull, but the operation went horribly wrong. A scuffle ensued, and an Indian policeman shot Sitting Bull in the head. As word spread, Indians exited the area.

Some of the fleeing Indians—a wagon train of about three hundred men, women, and children from the Miniconjou tribe—were stopped by US Army troops. The soldiers ordered them to return with them to their camp near Wounded Knee Creek.

The next day, on December 29, the Indians were ordered to turn in their guns. Some were surrendered, but the soldiers believed there were more, so they went from tent to tent, pulling out knives and other weapons. The soldiers, now about five hundred strong, were tense, having read newspaper articles about how the Ghost-Dancing Indians were preparing for war.[ One Indian—some say he was deaf, others that he was crazy—raised his gun in the air, declaring in Lakota that he had paid good money for the new Winchester and was not about to give it up. The soldiers grabbed him, and a shot was fired into the air.

Hundreds of soldiers opened fire on the Indians. Two-pound shells from the Hotchkiss cannons poured down. In just a few minutes, two hundred Indian men, women, and children were dead, along with twenty-five soldiers, most of whom were killed by friendly fire. Women and children who tried to flee the scene were shot as they ran. Bodies were found almost two miles away from the scene. One witness reported seeing a newborn infant nursing from its dead mother’s breast. Another recalled: “I saw a boy and a girl, probably 8 or 10 years old, running from the field in a southeast direction toward the creek, and I saw two soldiers drop down each on one knee, and taking a knee and elbow rest of their pieces, kill these little children who, when hit, carried by the momentum of running, went rolling over.”[

After the massacre, snow buried the dead. A cleanup party was sent on January 1, 1891, but the bodies were frozen under the bloodstained white covering. Yet several babies were found alive, lying beside their dead mothers. Other victims were frozen in grotesque positions where they had fallen.

Some children were wearing their school uniforms. The soldiers stripped many of the bodies naked—in part to get the “ghost shirts” as souvenirs—and 146 frozen bodies were dumped into a mass grave.

Most of the public reaction was positive. Twenty of the soldiers were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

It would be an exaggeration to say that the massacre at

Wounded Knee was primarily an act of religious violence. Economic, social, and

political factors helped fuel Indian passions and white paranoia. But the whites’

inability to see the Ghost Dance as a religious phenomenon—thanks to their deep

ignorance of, and arrogance about, Native American spirituality—led them to

wildly misinterpret its significance. They also underestimated the rage that

suppressing it would cause. Whites didn’t view their war on the Ghost Dance as

an assault on religious freedom, but the Indians surely did.