Nast-y Anti-Catholic Cartoons

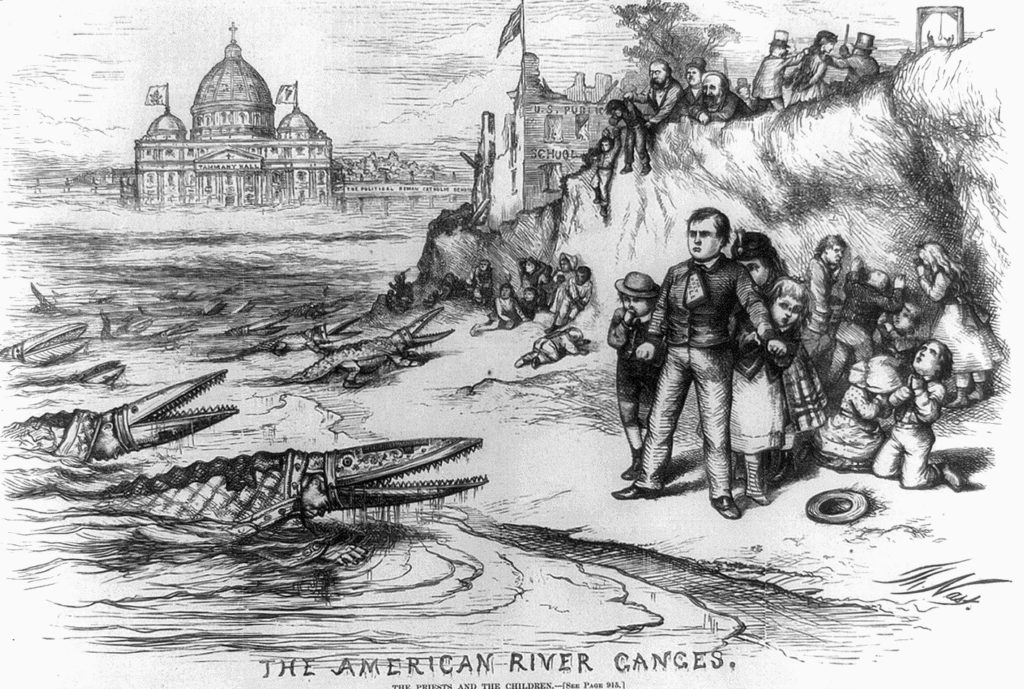

Look closely: those crocodiles coming ashore to eat the children are actually Catholic Bishops! The boy standing bravely on the beach has a Holy Bible sticking out of his coat. A gutted building behind them is labelled Public Schools. What’s this all about? In the 1870s, when this Thomas Nast cartoon was published, Protestants were aggressively casting Catholics as anti-Bible. The reason: the Catholics resisted having their kids forced to read the King James version of the Bible (instead of a Catholic translation).

Anti-Catholicism has been a powerful force for most of American history. In the second half of the 19th century, this could be seen in the cartoons of Nast.

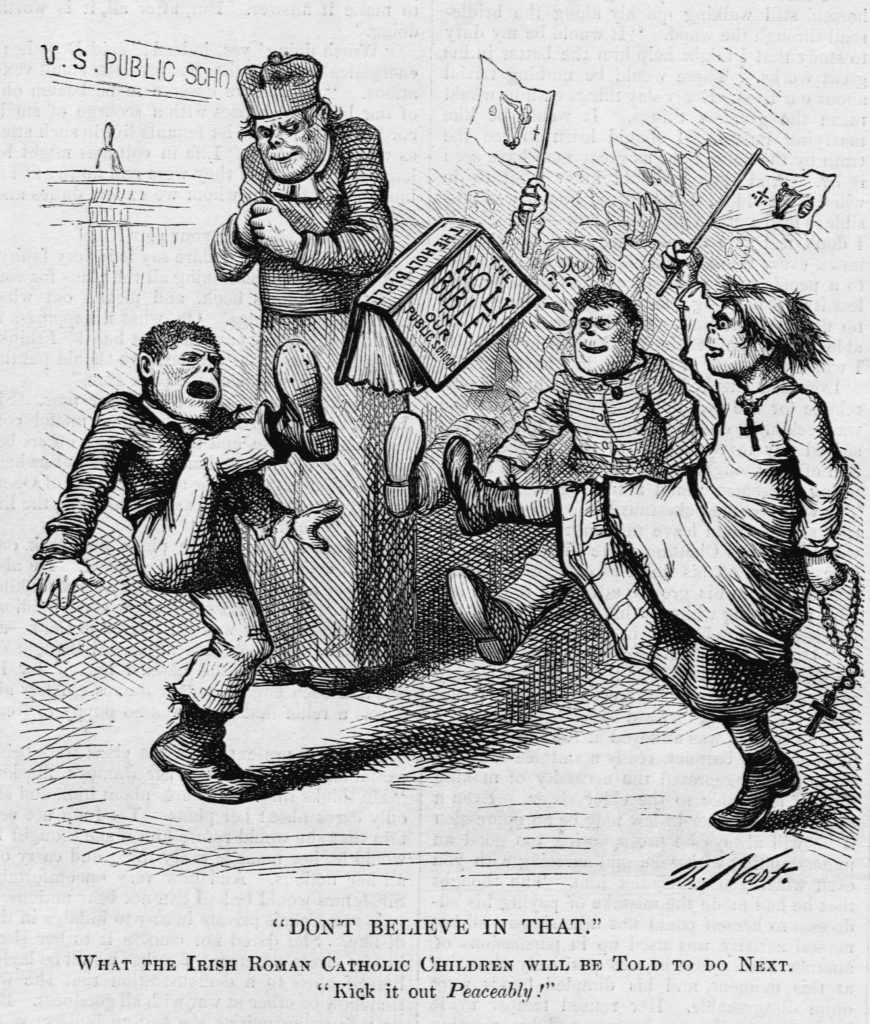

Notice how Irish Catholics were drawn to look somewhat like African Americans. That enabled opponents of Catholics to harness antagonism toward African Americans in service of their anti-Catholicism. This Nast cartoon, which appeared in Harpers, refers to a Bible-in-the-schools controversy that erupted in Long Island City, Queens, in 1875. The school board had required children to read from the King James Version of the Bible. Catholic students could either sit in the room during the exercise or leave for the day. In a gutsy form of civil disobedience, the Catholic children responded by blocking their ears as the principal read from the Bible. As the weeks went on, some students also shouted, “I don’t believe in that!” They kick the Holy Bible in the air as a bishop looks on with a sinister grin.

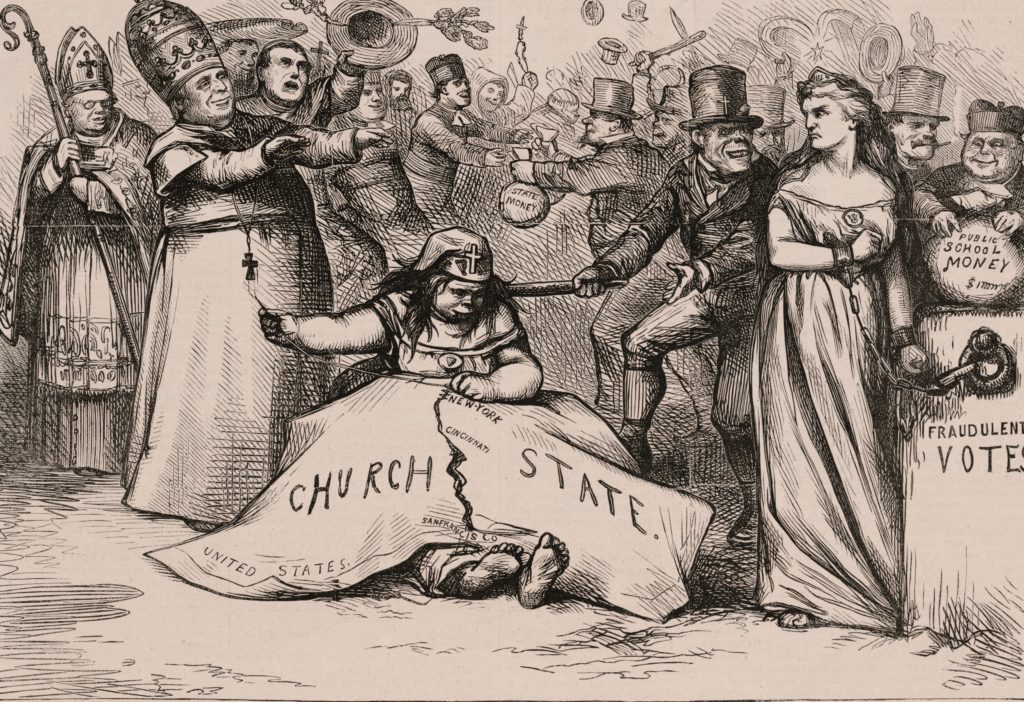

In the above Nast cartoon, an ape-like Catholic nun is sewing together church and state. Get it? The not-to-subtle message is that American Catholics wanted to destroy the sacred system of separation of church and state. Indeed, a quick way to signal your anti-Catholic bona fides was to declare your support for separation. Note, too, the simian Irishman sneering at Liberty who is chained to a bucket of “fraudulent votes.” Protestants accused Catholics of wanting state money to subsidize Catholic schools, which did happen in New York City but rarely elsewhere. The more common fight: Catholics resisted Protestant attempts to force Catholic school children to read the King James version of the bible, which they viewed as a “mutilated” translation.

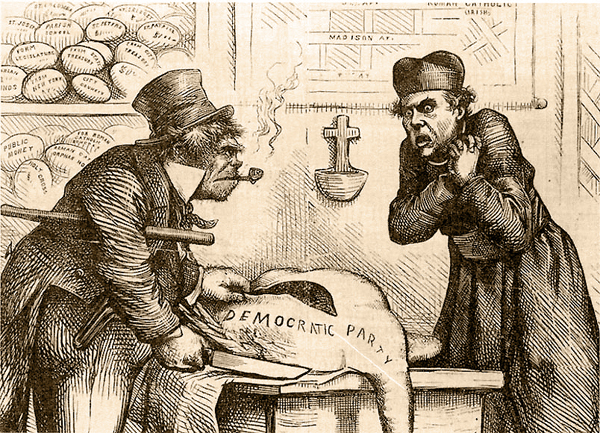

Needs no explanation.

For Nast, there was little difference between Irish Catholics, the Democratic Party and the Catholic Church. They were all sinister.

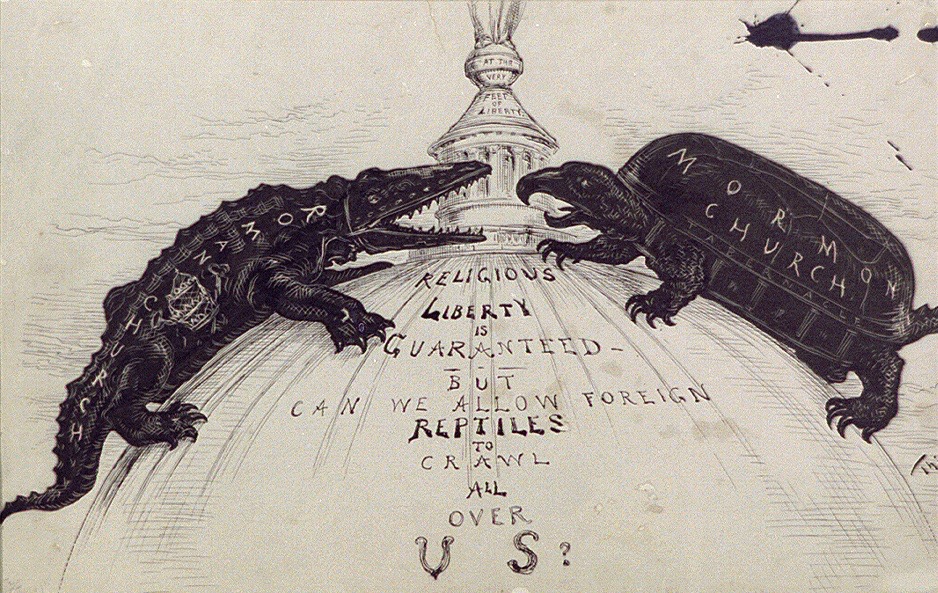

This cartoon, published in 1880 in Harpers, showed that Nast (and others) viewed Mormons as being equally nefarious — and comparable in being politically potent and supposedly opposed to religious liberty. This was a common technique: to undermine another religion’s freedom accuse them of being opposed to religious liberty.

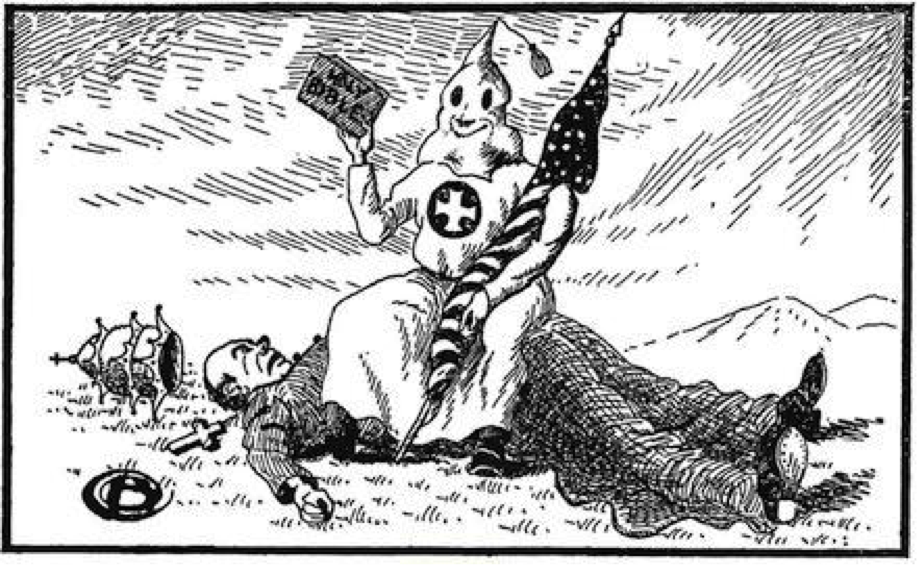

Fast forward to the 1920s and the cartoons take on a different focus. Anti-Catholism is again on the rise, this time with the second incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan casting themselves as the saviors of Protestant America.

Note how the cheerful KKK hero is holding the Holy Bible. Throughout the 19th and much of the 20th century, a major (false) claim was that Catholics wanted to prevent schools from teaching the Bible. Actually, Catholics opposed the reading of the King James Bible.

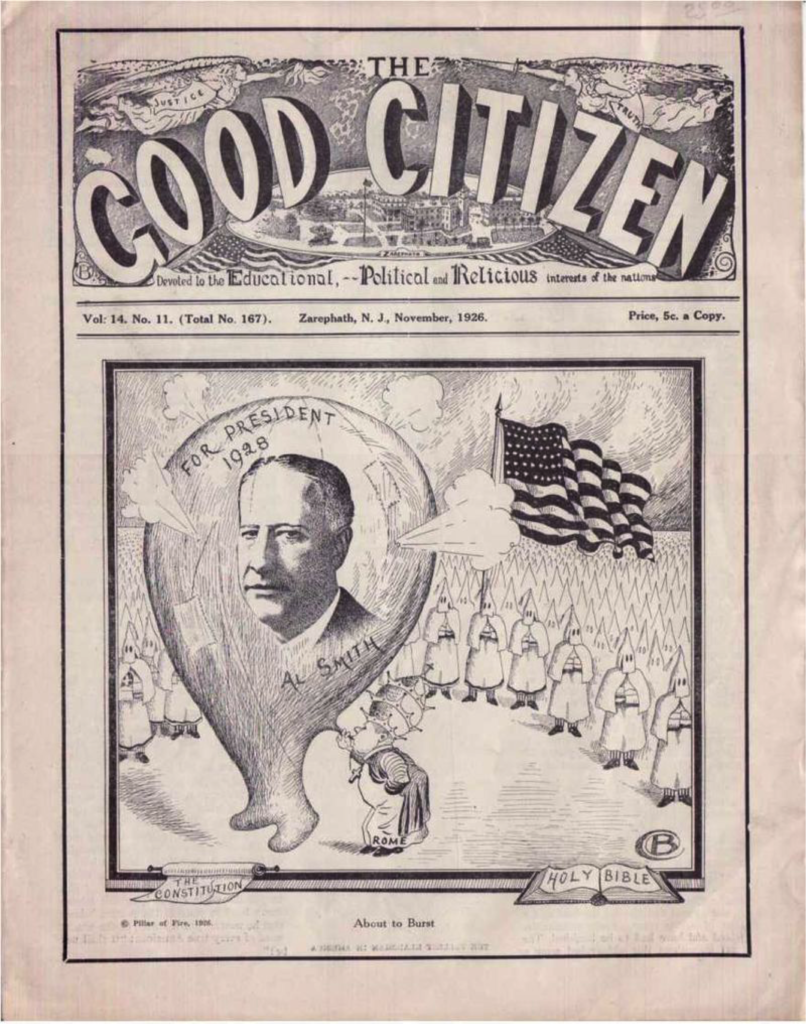

In 1928, the Klan’s focus turned to Democratic nominee Al Smith.

At the Democratic convention in Houston, where Smith was nominated, several Klansmen dragged a life-size effigy of Smith into the convention hall, slit its throat, and threw fake blood on its chest. Throughout the campaign, Smith was depicted as the pope’s puppet. Klansmen claimed that a photo of the recently completed Holland Tunnel in New York City actually showed a newly built secret pathway from Rome to the United States, through which the pope would arrive and take over the country. Around the country, signs appeared making it clear what the main issue was: “For Hoover and America, or For Smith and Rome. Which?” One KKK flier showed an image of a priest throwing a baby into a fire, with the title “Will It Come to This?” In Muncie, Indiana, a twofer conspiracy theory spread: the Catholics had invented a powder that would bleach the skins of black men so they could seduce and marry unsuspecting white women. Other fliers claimed that if Smith were elected, Protestant marriages would be annulled. As Smith arrived in Oklahoma City, he could see the burning crosses of the KKK across the countryside.

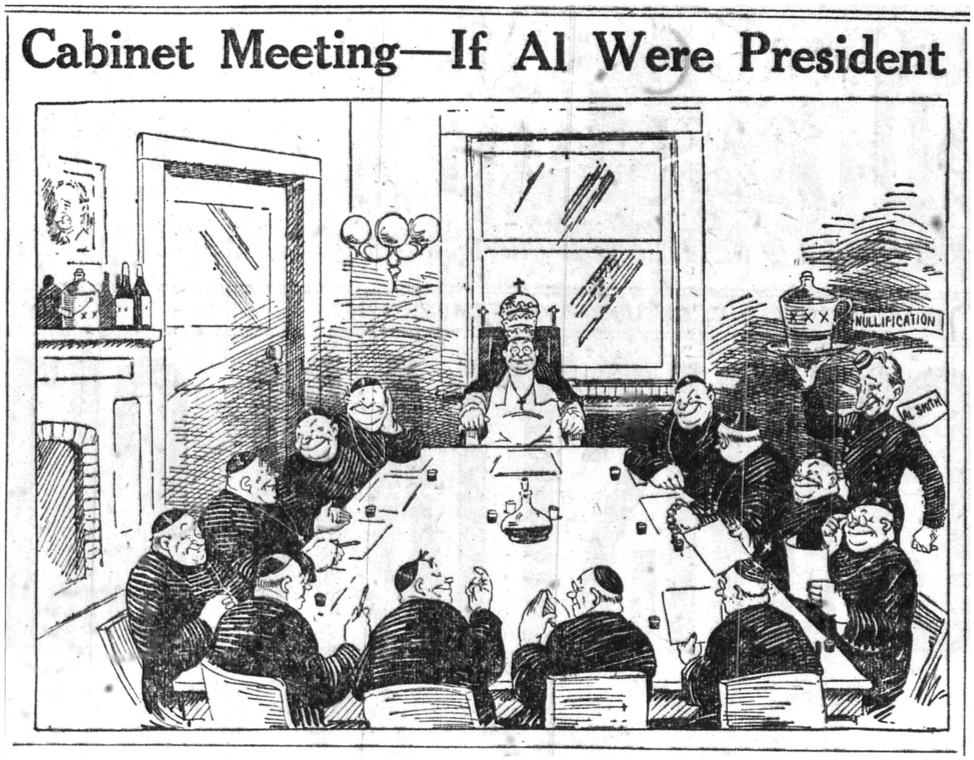

Al Smith is over on the side, dressed as a servant, carrying jug of booze over to the table of Cardinals. For religious Protestants, it was hard to disentangle Smith’s Catholicism from his opposition to prohibition. The temperance movement had always had anti-Catholic elements, viewing drinking, immigration, and urban squalor as branches of the same vine. In 1916, the Prohibition Party even included in its platform a call for “absolute separation of church and state.” Smith’s opponents called him Alcohol Smith and spread false rumors that he was a drunk. The popular evangelical preacher Billy Sunday referred to Smith’s supporters as “the damnable whiskey politicians, the bootleggers, crooks, [and] pimps.”87 Most creatively, John Roach Straton, the minister of New York’s Calvary Baptist Church, preached that Smith represented “card playing, cocktail drinking, poodle dogs, divorces, novels, stuffy rooms, dancing, evolution, Clarence Darrow, overeating, nude art, prize fighting, actors, greyhound racing and modernism.” Historians offer no explanation for how stuffy rooms and poodles got on the list.