“An Enemy Inside Our Perimeter”

A major attack on religious freedom is launched against American Muslims, accelerated by a new kind of media and a new kind of leader.

Excerpted from Sacred Liberty

Earlier in American history, those who wanted to suppress a particular religion had to confront a challenging question: Doesn’t doing that violate the First Amendment?

They often gave a brazen response: no, it doesn’t, because the despised minority faith in question wasn’t really a religion, at least not in an appropriate way. This claim was made about Mormons, Catholics, and Native Americans. Whenever this argument has surfaced, egregious assaults on religious liberty were sure to follow.

So it was ominous when, in 2007, the popular Christian televangelist Pat Robertson said, “Ladies and gentlemen, we have to recognize that Islam is not a religion. It is a worldwide political movement bent on domination of the world. And it is meant to subjugate all people under Islamic law.” Over the next decade, the claim that Islam was not a legitimate religion gained popularity. Echoing Samuel Morse’s comments about Catholics, Michael Flynn, Donald Trump’s main campaign advisor on national security, declared that “Islam is a political ideology. It definitely hides behind being a religion.” Ben Carson, the former surgeon and presidential candidate who became secretary of housing and urban development, said that Islam is “a life organization system,” not a religion. Steve Bannon, the former head of Breitbart News Network and an important early advisor to President Trump, told Mother Jones that Islam is “a political ideology.” In case there was any doubt about why they pushed this argument, the veil was lifted by retired Lieutenant General William G. “Jerry” Boykin, the deputy undersecretary for intelligence under President George W. Bush. Because Islam is “a totalitarian way of life,” he said, it “should not be protected under the First Amendment.”

To be clear, a noxious, fundamentalist strain of Islam is spreading and feeding the rise of global terrorism. The problem is not endemic to the en- tire religion, but it involves more than just a few extremists. At its worst, a bastardized version of Islam has energized or provided a pretext for ISIS, Al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and other militant groups. In some parts of the world, Muslim hatred of the West is pervasive. A few years after 9/11, Osama bin Laden still had a favorability rating of 65 percent in Pakistan. The populations in Jordan and Morocco felt similarly. Some Muslim majority countries have picked the most barbaric elements of Islamic law to undergird their systems of justice. One of those nations, Saudi Arabia, has used its tremendous oil wealth to spread a radical form of the faith. Meanwhile, persecution of Christians is growing around the world, often (though not exclusively) driven by Muslim governments.

Moreover, some Muslims in the United States have embraced the idea that God wants them to kill innocent Americans. Radicalized American Muslims committed massacres at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, at a Christmas party in San Bernardino, at Fort Hood, and at the 2013 Boston Marathon. American law enforcement officials have no choice but to increase surveillance of Muslims, including, in some cases, at mosques. When politicians and journalists insist that terrorists are simply isolated actors, disconnected from any religious motives, they are as wrong as those saying that all Muslims are terrorists.

That said, the treatment of Muslims in America in recent years has constituted a historic, grotesque attack on religious freedom. Regressive ideas and actions that were once common, and then banished as beyond the pale, are back. Anti-Muslim activists have blocked the construction of mosques and cemeteries. They have wiped away distinctions between Muslim terrorists and Muslim Americans. They have asserted that Islam itself is so inherently depraved that most Muslims are, by definition, terrorists or terrorist sympathizers. Attacks on American Muslims have been disseminated and normalized via digital media, faster and more effectively than were attacks on other groups in earlier eras. And we have witnessed the election of a president who made hostility to one American religion a centerpiece of his campaign. All in all, we’ve seen a revival of patterns we thought had been expunged, to such a degree that religious freedom itself now seems more precarious than it has in decades.

The Growth of Anti-Muslim Activism

President Bush delayed anti-Muslim sentiment from taking root,6 but within a year or two, conservative Christian leaders started taking a different tack. A stark example of the shift in approach among evangelical leaders can be found within the family of the beloved Christian evangelist Billy Graham. While he had complimented Islam in 1997, his son Franklin Graham in 2002 called Islam a “wicked, violent religion.” Later, he mocked Bush’s “Islam is peace” line. “There was this hoo-rah around Islam being a peaceful religion,” he said. “But then you start having suicide bombers, and people start saying, ‘Wait a minute, something doesn’t add up here.’” The dam broke, and other Christian leaders rushed in to criticize not only the terrorists but the Islamic religion and its founder. Jerry Falwell called Muhammad “a terrorist.” Jerry Vines, the former head of the Southern Baptist Convention, the nation’s largest Protestant denomination— the sect that had led the charge for religious freedom in the eighteenth century—called Muhammad a “demon-possessed pedophile.” The Christian book industry quickly capitalized with titles such as The Everlasting Hatred: The Roots of Jihad; Religion of Peace or Refuge for Terror?; and War on Terror: Unfolding Bible Prophecy.

Public opinion shifted dramatically. Immediately after 9/11, only 25 per- cent of Americans said “Islam is more likely to encourage violence,” but by July 2004, 46 percent did. Verbal attacks then morphed into concrete assaults on Muslims’ religious freedom—including one of the most basic, the freedom to establish houses of worship. In Tennessee, the Islamic Center of Murfreesboro had been established in 1982 for Muslim families in the community, about thirty miles outside Nashville. The Muslim population grew with the arrival of refugees fleeing Saddam Hussein and of Somalis displaced by civil war. Many other international students came to attend nearby Vanderbilt University and Tennessee State University. As of 2010, about one thousand Muslim families were sharing a 1,200-square- foot space to worship; the women watched on closed-circuit television in a converted garage. Members raised $600,000 for a new 12,000-square-foot building located on the outskirts of town. With the support of the Re- publican mayor, the city planning commission approved the mosque. But after word of the project spread, protests began.

The campaign against the Murfreesboro mosque featured many elements found in past assaults on religious minorities. First, fearful of genuine Islamist terrorism, local residents lost the distinction between radicals in Afghanistan and restaurant owners in Murfreesboro. After someone set fire to construction equipment at the mosque site, one resident said, “I think it was a piece of their own medicine. They bombed our country.” Another agreed that the “they” over there were the same as the “they” next door. “Everybody knows they are trying to kill us,” she declared. “Somebody has to stand up and take this country back.” Another said, “Something’s going on, and I don’t like it. We’re at war with these people.” A billboard appeared declaring “Defeat Universal Jihad Now.”

Second, they too maintained that Islam was not a real religion and therefore not worthy of First Amendment protection. Ron Ramsey, a candidate for lieutenant governor, suggested, “You could even argue whether being a Muslim is actually a religion, or is it a nationality, way of life, cult or whatever you want to call it?” A local Republican candidate for the US House of Representatives, Lou Ann Zelenik, explained that Islam was a political organization “designed to fracture the moral and political foundation of Middle Tennessee.”

Third, they flipped the script and claimed that it was the Muslims who were endangering the religious freedoms of non-Muslims. In one of the lawsuits filed against the mosque, opponents argued that mosque members were “compelled by their religion to subdue non-Muslims.” Therefore, “why would we give any religion the right to cancel our rights under the United States Constitution?”

Encouragingly, despite local opposition, the courts upheld the basic principles of religious freedom. A local judge at first ruled for the protesters, finding that the planning commission had not given adequate notice of the meeting at which the permit was approved. But a US district court ruled that the mosque could open, and other courts agreed. The US Department of Justice helped by filing a brief explaining that Islam is, indeed, a religion.

Efforts to block Muslim houses of worship were not limited to Tennessee. In 2012, the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life counted at least fifty-three instances when proposals for mosque construction or expansion were contested by local residents. When the Islamic Society of Milwaukee applied for permission to build a mosque, a rally was held to protest “the growing threat of Islam.” One resident explained that “a mosque is a Trojan Horse in a community. Muslims have not come to integrate but to dominate.” During a zoning board meeting in Bayonne, New Jersey, residents railed against the “so-called religion.” Protests against a mosque in Temecula, California, drew signs such as “Mosques are monuments to terrorism.” A local pastor said: “I see people blowing up, being killed, beheaded, murdered, every day in the news. And I see that they are very often—virtually all the time—they have a Muslim connection. I don’t see every day in the paper Baptists beheading, killing, burning, looting, suicide bombing.”

The protests became so prevalent that the United States Department of Justice stepped up its efforts to intervene. From 2010 to 2016, the Justice Department joined or initiated seventeen cases in which, it believed, opposition to mosque construction violated the religious freedom of American Muslims. For instance, the Justice Department argued in a case in Culpeper County, Virginia—the same county where Baptists had been persecuted in the time of James Madison—that on twenty-six other occasions the town had approved the type of permits that it denied the mosque.

Even deceased Muslims scared the increasingly agitated populace. Residents in at least four communities attempted to block Muslims from creating cemeteries. West Pennsboro Township, Pennsylvania, objected on the (false) theory that Muslims’ burial practices would contaminate the groundwater, since they don’t place caskets in metal-lined vaults. In Farmersville, Texas, residents officially complained about the location of the cemetery, but some were up front about the real roots of their opposition: “People don’t trust Muslims. Their goal is to populate the United States and take it over,” one resident said. Town leaders tried to reassure residents by distributing material stating that there would be “no terrorist activity associated with” the cemetery.

The Sharia Scare

In 2010, Newt Gingrich, the former Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives, urged a mainstream conservative audience at the prestigious American Enterprise Institute to wake up to a new enemy. It was not ISIS, nuclear proliferation, immigration, or social polarization. No, it was something called “Shariah” that was “a mortal threat to the survival of freedom in the United States and in the world as we know it.” To casual observers this may have seemed like a quixotic obsession, but Gingrich was tapping into a growing fear that Islamic law, with associated barbaric punishments, was infiltrating America. From 2010 to 2016, lawmakers introduced 120 anti-Sharia laws in forty-two states. In Tennessee, a bill provided for a fifteen-year prison sentence for anyone who helped a “Sharia organization,” which was defined as two or more people acting to “support” Sharia. Six states—Louisiana, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Arizona, Kansas, and South Dakota—approved laws aimed at blocking Sharia. Conservative funders bankrolled the placement of 28 million copies of Obsession, a video about Islamic terrorists, in seventy newspapers. Sharia was “the pre-eminent totalitarian threat of our time,” declared an urgent report from the Center for Security Policy, a leading anti-Islamic activist group run by a former official of the Ronald Reagan administration named Frank Gaffney.

To be clear, the Sharia threat in America is made up. Yet it gained prominence and legitimacy with stunning speed—exemplifying how the modern techno-media system can turbocharge attacks on religious freedom.

Sharia law refers to a broad set of religious rules assembled over hundreds of years to guide Muslim behavior. It covers religious and ethical practices—such as how many times a day to pray, what kinds of food Muslims should eat, how to treat animals, what kind of loans are permissible— and a wide variety of other topics. It addresses family law, including rules for marriage, divorce, and inheritance. It can, in some countries, include legal punishments for crimes; in a handful of Muslim countries, authorities even cite the Quran in occasionally cutting off the hands of thieves. Mostly, Sharia is similar in nature to the Halacha rules that govern some Orthodox Jews and to Catholic Canon Law, which affects all practicing Catholics.

Anti-Muslim activists have thoroughly distorted both the content of these rules and how they’re used by Muslims around the world. They describe Sharia as a take-it-or-leave-it, all-inclusive package of rules that all Muslims around the world must, and do, follow. Sharia, they say, requires violent jihad against nonbelievers, so Muslims within the United States will inevitably follow those orders. Violence, barbarism, sexism, and hatred of democracy will grow as American courts and communities are forced to accept Sharia.

Let’s start with the most basic point. For any particular Sharia rules to become law in the United States, they would have to be approved by state legislatures and city councils. The same is true for Halacha and Catholic Canon Law. Orthodox Jews may opt to eat only kosher food, but to block other Americans from eating shellfish, the United States Congress would need to ban lobster rolls. Same with Sharia. Muslims can use parts of Sharia as a private personal code, but to force it on other Americans, those rules must be approved by state legislatures or Congress. It is true that civil courts are sometimes asked to adjudicate cases in which individuals have made contracts or decisions based on their personal religious views. For instance, a couple who divorced following the procedures of a rabbinical or Sharia court might then present that agreement to an American court for enforcement. The courts pretty much treat these the way they treat other contracts, assessing factors such as whether they were created under duress or violate American laws. To do that, judges sometimes need to understand the nature of those religious rulings. But American courts do not accept the contracts if the terms violate American law.

The second fallacy is that if a Muslim abides by any of Sharia’s rules, he or she must abide by all of them, following the most extreme possible interpretations. In other words, if you eat halal chicken and rice, you pretty much have to kill infidels too. In fact, on this score, Islam is like, well, every other religion in the history of the world: its practitioners have interpreted religious law in a wide variety of ways. There are certainly fundamentalist countries that interpret the Quran to justify inhumane rulings. For instance, 85 percent of those in Afghanistan believe in stoning as a punishment for adultery, and even in the more moderate Turkey, 29 percent agree. But the idea that Sharia requires opposition to democracy is widely rejected by Muslims around the world. Some 93 percent of Muslims in Indonesia say it is “good that others are very free to practice their faith.” Even among Muslims who do want Sharia applied pervasively, many believe it should apply only to Muslims.

Of course, the real worry for the American political system should be whether American Muslims want Sharia imposed. They don’t. Not a single major American Muslim group has asked for Sharia to be enshrined in the American legal system. While 79 percent of Muslims in the world said Sharia should be “a source” for legislation, just 37 percent of American Muslims did. And many Muslims say they support Sharia in the same way that 55 percent of Americans say the Bible should be a source for legislation. They mostly mean biblical values should inform the law, not that judges should, say, adopt the suggestion in Deuteronomy that rapists be required to marry their victims. Most American Muslims say there are multiple valid interpretations of Islam, and only one-third even say Islam is the “one true faith,” about the same percentage as American Christians who make that claim for their own religion. American Muslims benefit more from religious freedom than any Muslims in the world; they’re not eager to trade American law for the rules of Pakistan. In fact, 66 percent of American Muslims believe life here is better than in most Muslim countries, compared with 8 percent who say it’s worse.

Catholics in the 1830s, in the 1920s, and in 1960 had to answer a similar charge that they owed allegiance to a foreign authority and set of laws. In his attack on Al Smith in 1929, Charles C. Marshall argued in the Atlantic that if a Catholic were elected to the US presidency, decision making on marriage, education, and other topics would be “wrested from the jurisdiction of the State.” Catholics would have no choice but to obey the “foreign and extraterritorial” rules. American Muslims are freer to ignore fundamentalist interpretations of Sharia than Catholics of the 1920s were in disregarding the Vatican.

In short, American Muslims have not tried to impose Sharia and don’t want to—and even if they did want to, they couldn’t.

In truth, most of those warning about Sharia were not taken seriously for much of the 2000s. Anti-Islam activist Frank Gaffney was excluded from some conservative political gatherings because of his fringe views. Then, starting around 2010, the anti-Sharia movement began to take off. When controversy erupted in New York over plans—approved by local authorities and churches—to construct an Islamic community center a few blocks from the site of the World Trade Center, Sharia became part of the opposition campaign. Robert Spencer of Jihad Watch explained how the center would invariably spawn terrorism. “They say it will be different but they will be reading the same Quran and teaching the same Islamic law that led those 19 hijackers to destroy the World Trade Center and murder 3,000 Americans.”

The battles over anti-Sharia laws in the state legislatures intensified. In November 2010, the voters of Oklahoma approved the Save Our State amendment to the state’s constitution, which decreed that their courts “shall not consider international law or Sharia law.” State senator Rex Duncan, the sponsor of one anti-Sharia bill, admitted that there were no examples of Sharia being imposed but claimed that the bill was a “preventive strike” to help ensure “the survival of America.” The bill’s other sponsor, Representative Mike Reynolds, explained, “America was founded on Judeo-Christian values, it’s the basis of our laws and some people are trying to deny that.” After a federal judge, Vicki Miles-LaGrange, struck down the amendment, Robert Spencer reposted an article titled “Taliban Chops Off Man’s Hand for Theft” and asked, “Isn’t it great that Judge Vicki Miles-LaGrange has made Oklahoma safe for Sharia?”

Being against Sharia became a way for lawmakers to signal their conservative toughness. A stunning 630 different Republican legislators sponsored or cosponsored anti-Sharia laws from 2010 to 2016. Since Sharia was thought of as an indivisible package, they figured even minor accommodations to Muslim traditions would lead inexorably to adoption of full Sharia. When schools in Dearborn, Michigan, began providing halal meals for their large Muslim population, Pamela Geller’s organization tweeted, “Halal meals increasing in Dearborn schools. What’s next???” When some cities set aside female-only swim times in public pools, in part to accommodate Muslim women, Geller pleaded, “Stop the Islamization of America.” She reported that “in a little-known strike against freedom,” Butterball turkeys were slaughtered in a halal-compliant way and should be boycotted. Bryan Fischer of the American Family Association seriously warned, “Every single Butterball turkey sold in the United States of America has been sacrificed to Allah.”

Like the argument that Islam was not a religion, the anti-Sharia drive could be used to break apart First Amendment protections. “Far from being entitled to the protections of our Constitution under the principle of freedom of religion,” Frank Gaffney wrote, Sharia “is actually a seditious assault on our Constitution which we are obliged to prosecute, not protect.” Claiming that “over eighty percent” of American mosques are “shariah-adherent,” he concluded that they are not houses of worship but rather “incubators of, at best, subversion and, at worst, violence and should be treated accordingly.” A report issued by his Center for Security Policy, signed by numerous notable anti-Muslim activists, recommended a stunning array of legal restrictions for those who “espouse or support shariah,” that is, most American mosques:

- Muslims who back Sharia should be prohibited from holding elective office or serving in the military.

- “Shariah-compliant”finance(i.e., Islam-friendly financial products) should be banned.

- Mosques that “advocate shariah in America” must be “subject to investigation and prosecution.

Imagine the above sentences with “Catholic Canon Law” or “Jewish rules of Halacha” substituted for the word “Sharia”: Jews who espouse or support Hebrew law should not be allowed to hold public office. Catholic churches that advocate the use of Catholic Canon Law must be subject to investigation and prosecution. The practical damage of these laws has so far been limited. In 2012, a US court of appeals ruled that the Tennessee law violated the First Amendment’s religious freedom protections. Later state efforts more narrowly tailored the attacks toward blocking the influence of “foreign laws” in general rather than just Islamic law.

Just as important, other religious groups joined the fight against these laws, seeing that such a flagrant attack on religious freedom would inevitably hurt them too. An organization representing Orthodox Jews concluded that the laws undermined Jewish religious courts, the beit din, and “would be a terrible infringement on our religious freedom.” Weighing in on a proposed law in Arizona, an alliance of Jewish groups said, “It would apparently prohibit the courts from looking to key documents of church, synagogue or mosque governance—religious law—to resolve disputes about the ownership of a house of worship, selection and discipline of ministers, and church governance.” Abraham Foxman, the longtime head of the Anti-Defamation League, had a nonlegal explanation for the anti- Sharia movement. “People don’t know what Sharia means, it’s a foreign word,” Foxman told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. The proposed anti-Sharia laws, he said, are “camouflaged bigotry.”

Rotten to the Core

The anti-Sharia attack was part of a larger drive by anti-Muslim activists to destroy George W. Bush’s initial framing. Islam had not been hijacked but rather was rotten to its core. Terrorists commit terror, they argued, because they’re good Muslims, not because they’re bad Muslims.

Their most important contention: Islam is inherently violent. It’s quite easy to make a misleading but plausible-sounding argument to that effect. Terrorists shout “Allahu Akbar!” as they murder innocents. Some Muslim clergy declare that the Quran supports suicide bombers. And passages in the Quran promote violence. In these arguments, conservatives have been joined by some liberals and libertarians such as Bill Maher and Sam Harris.

The first flaw in the arguments is that many of the Quranic quotes are torn out of their contexts and sometimes amputated as well. Muhammad was a military leader defending Muslims from attacks; in that historical context, the Quran was partly a battle guide. Muhammad urges his troops to attack, but once victory is at hand, to relent. Critics often quote the passage “Kill them wherever you find them.” They often leave off the rest of the quote: “But if they desist, then lo! Allah is forgiving and merciful.”

Second, while there’s plenty of violence in the Quran, it’s really no worse than the Bible. In addition to oft-quoted messages of peace, both the Old and New Testaments include scenes that make the Quran seem like Teletubbies. For instance, Yahweh decrees that because the people of Samaria rebelled, they will have “their pregnant women ripped open.” The psalmist offers this message for the Babylonians: “How blessed will be the one who seizes and dashes your little ones against the rock.” While hard-line orthodox Muslims target “nonbelievers,” the New Testament makes clear the fate awaiting those who do not accept Jesus: “In flaming fire taking vengeance on them that know not God.”

Some modern Christians acknowledge that the Olde Time believers— the Crusaders or the leaders of the Spanish Inquisition—deployed their faith in the service of violence too. But, they say, Christians have matured, while Muslims have not. There’s an element of truth to that; in the twenty-first century, religiously motivated violence more commonly arises in predominantly Islamic countries than in Christian countries. But Christians shouldn’t get cocky. Biblically ordained sadism is found in recent history. To take just one example, in 1992, Christian Serbs put Bosnian men and boys in concentration camps for the crime of being Muslim. Serbian sharpshooters on the heights above Sarajevo shot down pedestrians in the streets as if they were hunting fowl. Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic justified his 1992–95 campaign of ethnic cleansing as “just and holy.” Here in the United States, it was just a few generations ago that American Christians used the Bible to justify slavery. Leviticus 25:44–46 was cited often: “Your male and female slaves are to come from the nations around you; from them you may buy slaves.” The Richmond Enquirer concluded, “Whoever believes that the written word of God is verity itself, must consequently believe in the absolute rectitude of slave-holding.” Bans on interracial marriage, which survived until 1967, sometimes rested on biblical justifications. More recently, Christian op- position to the morality and even the legality of homosexuality has relied heavily on passages from the Bible.

The point is not that the holy books, or the faiths, are equal (or unequal) but that the reality of religious practice has always been deter- mined by how believers interpret doctrine at that moment in time. Some Muslims—far too many—are choosing to deploy the Quran in the service of violence, sexism, bigotry, and even terrorism. But most are not— including, crucially, almost all the Muslims in the United States. Perhaps the best proof that Islam isn’t inherently regressive is how American Muslims practice it.

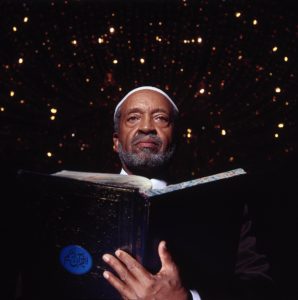

Anti-Muslim activists ignore the ways in which American Muslims have attempted to chart a new course for Islam. “We should not look to the Muslim world any more for leadership,” declared W. D. Mohammed, probably the most significant Muslim leader in America, after 9/11. “The hope is not there. Don’t expect anything from these governments but more disappointment, until they repent.” He argued that the Quran and the Hadiths could guide American Muslims toward a truer form of the faith. “We see the world of Islam in the condition that it is in and that alone should make us more spirited, more courageous, more determined to establish a beautiful society of Muslims in America which is the highest mountain on earth in terms of government.”

In Taking Back Islam, published in 2002 by Beliefnet, American Muslims asserted the right to define their religion, just as American Catholics and Jews had before them. “September 11 forced a reckoning of sorts,” wrote Michael Wolfe, who edited the anthology.

And it has led us to be more self-reliant. When any religion

is new to a place, as Islam is new to America, the tendency to take one’s cues from the Motherland is strong, wherever that Motherland is perceived to be. And then there comes a moment to grow up. For many American Muslims, that moment arrived in the weeks following September 11, when a substantial number grew disenchanted with the habit of looking abroad for leadership. The near extinction of Afghanistan at the hands of the Taliban, the abysmal state of education in Pakistan, the murderous mullahs of al-Qaeda misquoting the Qur’an on video, along with a host of other glaring moral failures, have led many American Muslims to suspect that Islam’s “traditional lands” have less to teach us than they claim.

Not surprisingly, American Muslims have been in the vanguard of liberalization. Some 64 percent of them say there’s more than one way to interpret Islam. And 92 percent say they’re proud to be Americans, which is why it’s not so surprising that as of 2015 there were 5,896 Muslims serving in the US military. Those who find it difficult to believe that American Muslims may be patriots might write on the back of their hand these names: Daniel Isshak, Omead H. Razani, Humayun Saqib Muazzam Khan, Kendall Damon Waters-Bey, Mohsin A. Naqvi, James M. Ahearn, Kareem R. Khan, Rasheed Sahib, Azhar Ali, and Ayman A. Taha. They are Muslim American soldiers who died defending their country, the United States, after 9/11.

Ironically, the only two groups that truly believe that Islam requires violent jihad are the “murderous mullahs” and American anti-Muslim activists. Both groups would contend that truly devout Muslims should wage war against infidels. American Muslims such as Wolfe who do not share that interpretation are, well, just not reading their Quran carefully enough. Brigitte Gabriel, leader of ACT for America, claimed: “Behind the terrorist attacks is the purest form of what the Prophet Mohammed created. It’s not radical Islam. It’s what Islam is at its core.” If you’re a devout Muslim, you by definition cannot be a loyal American, she has argued. “A practicing Muslim who believes the word of the Koran to be the word of Allah, who abides by Islam, who goes to mosque and prays every Friday, who prays five times a day—this practicing Muslim, who believes in the teachings of the Koran, cannot be a loyal citizen to the United States of America.” Christian conservative leader Bryan Fischer put it clearly: “The greatest long-term threat to our security is not radical Islam but Islam itself.”

The casual assertion that American Muslims have no agency—or that if they dislike terrorism, it’s only because they’re sloppy Muslims—recalls the arguments of anti-Catholic activists in earlier eras. Even if well- meaning, Catholics had no choice but to follow Rome. There was little recognition of the myriad ways that American Catholics had been Americanizing Catholicism.

Destroying the Moderates

The George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations did not argue that Islam was flawless. Rather, they maintained that there was, in effect, a civil war within Islam—and therefore the most effective response was not only fighting radicals but also bolstering reformers and moderates. But American anti-Muslim activists had a different assessment: the moderates were terrorists in waiting. They began attacking mainstream American Muslims and Muslim institutions. Huma Abedin, Hillary Clinton’s top aide, was accused of connections to terrorists, a charge so baseless that several Republican senators came to her defense. Khizr Khan, the Muslim father who spoke at the 2016 Democratic National Convention about his son who was killed fighting in the US Army in Iraq, was subsequently attacked as a terrorist sympathizer because he criticized the Republican presidential nominee. InfoWars.com, a popular conspiracy website that became main- streamed during the 2016 election, ran an article with the subhead “Khan Defends Sharia Law Responsible for the Executions of Gays and Women in 11 Countries.” A reality TV show, All-American Muslim, depicting the lives of regular Muslims, was boycotted by the Florida Family Association, a conservative evangelical group, on the grounds that it was “propaganda clearly designed to counter legitimate and present-day concerns about many Muslims who are advancing Islamic fundamentalism and Sharia law.”

And then there was the demonization of Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, the would-be builder of the Islamic center in lower Manhattan (to have been called Cordoba House, in homage to the area of Spain where Muslims, Jews, and Christians ostensibly lived together harmoniously in the tenth century). Rauf had been one of the nation’s leading advocates for interfaith cooperation and a regular denouncer of Islamic terrorism. The Bush administration hired him after 9/11 to speak in other countries about the status of Muslims in America, with one official explaining in 2007, “His work on tolerance and religious diversity is well-known and he brings a moderate perspective to foreign audiences.” But after he advocated creating the Islamic community center—including a swimming pool, basketball court, and library—in lower Manhattan, he was recast as a bin Laden clone who wanted to build a “victory mosque” to celebrate 9/11.

On FOX & Friends, Newt Gingrich argued, “Nazis don’t have the right to put up a sign next to the Holocaust Museum in Washington.” Sean Hannity declared, “I’m not talking about shredding our Constitution and putting Sharia law as the law of the land in America, as [Rauf] is,” and at another point asked, “Should he even be in the U.S.?” Hannity’s evidence that Rauf wanted to shred the Constitution? Rauf’s assertion that America already is “Sharia compliant” because it “upholds, protects, and furthers” the “God-given rights” of “life, mind (that is, mental well-being or sanity), religion, property (or wealth), and family (or lineage and progeny).” Rauf was making the argument that real Islam is fully compatible with democratic values—and he was attacked for it. The physical threats against Rauf became so severe that police instructed him to live in a secret safe house for months during the controversy. His wife, the Muslim feminist activist Daisy Khan, received hate letters such as one that included an image of herself labeled “Daisy (the new face of terror) Khan=another whore of Muhammed.”

As with other religious groups in American history, not all Muslim groups have spotless records. One of the most controversial has been the Council on American-Islamic Relations, which has operated as a main- stream group defending Muslims against attack yet was founded by men affiliated with the radical Middle East group Hamas. But anti-Muslim activists paint with the broadest possible brush. The Islamic Society of North America—the same group that chose a feminist white woman as its president—was cast as a front for fundamentalist terrorist organizations. The anti-Sharia report by Frank Gaffney’s group, the Center for Security Policy, included in a list of “institutions supporting shariah law” bastions of American education, including the Section on Islamic Law of the Association of American Law Schools and the Islamic Legal Studies Program at Harvard Law School. The Center for Security Policy made it clear that mainstream Muslim leaders were among those to be feared: “We have an enemy inside our perimeter.”

Even those Muslims who happen to be doctors, basketball players, or congressmen should be scrutinized, they suggested, because most Muslims are at least terrorism sympathizers. Robert Spencer, one of the most quoted anti-Muslim activists, made the preposterous claim that 300 million Muslims around the world were poised to murder Westerners—and that those who weren’t willing to pull the cord on the suicide bomb vest were warmly supportive of those who were. “The Muslims who are not fighting still understand that that is something good and proper to be done and they applaud those who do it,” Spencer argued on FOX News. Former Wisconsin governor Scott Walker said during the 2016 Republican presidential campaign that there were a “handful of reasonable, moderate followers of Islam.” A handful.

One alleged “proof” that American Muslims are complicit in terror is that they supposedly never denounce terrorism. “There’s been a lot of silence in the Islamic community when America and Americans have been attacked by acts of terror from the Muslim community,” said Tony Perkins, head of the conservative Christian group the Family Research Council. Given the magnitude of the problem, Muslim leaders could no doubt do more—but they do a lot. In the years after 9/11, Muslim leaders issued hundreds of condemnations. Indeed, many not only denounced Islamic extremism but also took the far gutsier step of criticizing fundamentalist Muslim culture.

Ingrid Mattson, who has served as the head of the Islamic Society of North America, was quite candid about the clout of Muslim extremists.

Let me state it clearly: I, as an American Muslim leader, denounce not only suicide bombers and the Taliban, but those leaders of other Muslim states who thwart democracy, repress women, use the Qur’an to justify un-Islamic behavior, and encourage violence. Alas, these views are not only the province of a small group of terrorist or dictators. Too many rank-and-file Muslims, in their isolation and pessimism, have come to hold these self-destructive views as well.

Because American Muslims have both freedom and affluence, they have an obligation, she argued, to champion a more enlightened Islam. “Muslims who live in America are being tested by God to see if we will be satisfied with a self-contained, self-serving Muslim community that resembles an Islamic town in the Epcot global village, or if we will use the many opportunities available to us to change the world for the better—beginning with an honest critical evaluation of our own flaws.”

Despite this, people like Mattson have been attacked. Anti-Muslim activists have insisted that American Muslims are part of the problem—and that they refuse to help weed out terrorists. “When they see trouble they have to report it,” said Donald Trump. “They are not reporting it. They are absolutely not reporting it and that is a big problem.” In fact, the evidence is overwhelming that law enforcement has been able to thwart a huge number of attacks because of the cooperation of rank-and-file Muslim Americans. Out of the 120 violent terrorist plots that were thwarted between 2001 and 2015, the tips came from American Muslims in 48 of them.

The anti-Muslim crusaders cast American Muslims as the enemy within in order to build support for limiting their freedom. If American Muslims are anti-American and Islam isn’t really a religion, then taking steps to close mosques, ban Muslims from office, or refuse to accommodate legitimate religious practice don’t violate the United States Constitution. As Frank Gaffney’s Center for Security Policy put it, “Today, we are facing a threat that has masked itself as a religion and that uses the tolerance for religious practice guaranteed by the Constitution’s First Amendment to parry efforts to restrict or prevent what amount to seditious activities.” Even though antipathy to different religious groups has persisted throughout American history, opponents have rarely overtly argued that the unpopular groups should not be covered by the First Amendment. Yet that argument has been made repeatedly by anti-Muslim activists. In 2010, Harvard professor Martin Peretz, then editor in chief of the New Republic, an influential progressive, pro-Israel magazine, put it most baldly. “Muslim life is cheap, most notably to Muslims. . . . So, yes, I wonder whether I need honor these people and pretend that they are worthy of the privileges of the First Amendment which I have in my gut the sense that they will abuse.”

The Media’s Role

Why, when we’d come so far, have we suddenly experienced such a powerful threat to religious freedom? An entirely new media system has changed how such attacks congeal and metastasize. Granted, bigots in the past have gained national platforms. For instance, Father Charles Coughlin was given radio time to utter anti-Jewish tirades on national radio and Henry Ford published his anti-Semitic views in his newspaper. But their power tended to be limited in duration and breadth. For a while, that was true for anti-Muslim activists too. Over time, though, the activists- formerly-known-as-extremists gained massive clout and credibility thanks in part to the revolution in social media and the rise of a new conservative media establishment. One characteristic of social media, of course, is that voices on the margins can far more easily find audiences. That was certainly true for the anti-Muslim groups. According to author Nathan Lean, tweets sent by Pamela Geller had massive viral appeal, generating 150 million impressions for every 1,000 tweets (about three months’ work for her). Robert Spencer’s comments were retweeted 300,000 times, generating 81 million impressions during the 93 days he analyzed. In the month of July 2015 alone, 215,246 anti-Muslim tweets were sent. With reach came influence and ultimately respectability.

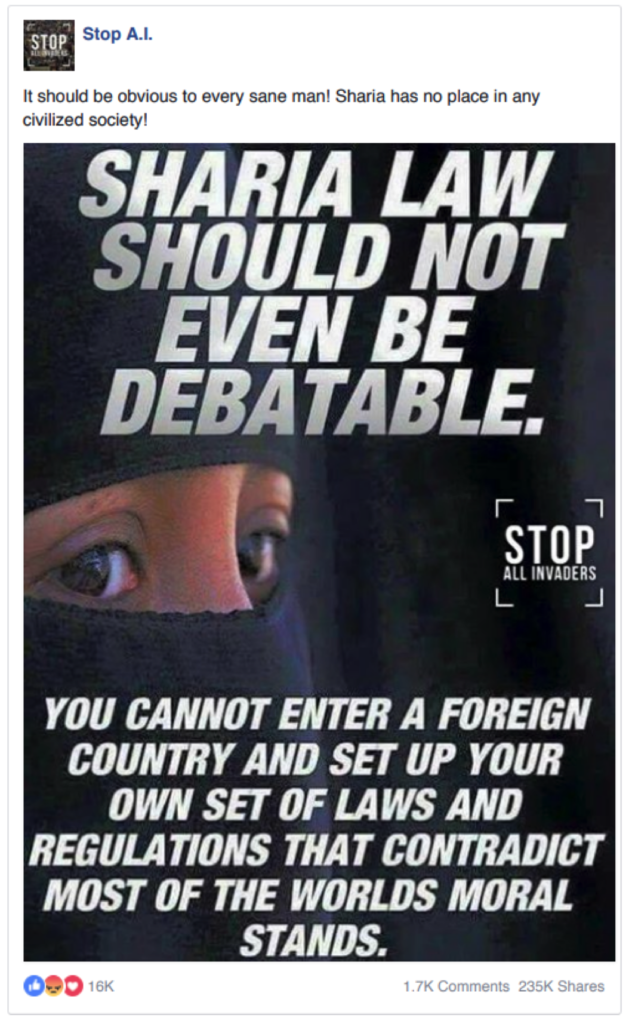

As if the social media engine weren’t powerful enough, they got some help from the Russians too. In order to destabilize American democracy, Russian hackers and operatives pushed inflammatory anti-Muslim con- tent. One Instagram post showed an image of a woman, eyes peering out of a black burka, and this message: “sharia law should not even be debatable. stop all invaders. you cannot enter a foreign country and set up your own set of laws and regulations that contradict most of the worlds moral stands.” It was shared 235,000 times. The Russians clearly decided that attacking Sharia would serve their goal of dividing Americans. They created a fake anti-Muslim group to organize a rally in Houston, Texas, in May 2016 and a fake pro-Muslim group to counter- protest. Innocent Texans, thinking the calls to action were real, attended the event, unaware that they’d been sent there by Russian hackers.

Leading conservative media outlets gave platforms to fringe figures. Robert Spencer, the one who said that 300 million Muslims were poised to strap on suicide vests, was regularly published by the Breitbart News Network, one of the most influential conservative news outlets, and appeared on the radio show hosted by Breitbart chief Steve Bannon, who called him “one of the top two or three experts in the world on this great war we are fighting against fundamental Islam.” Frank Gaffney, whose group called for the shutting down of most mosques, had appeared on Steve Bannon’s radio show twenty-nine times as of early 2017.

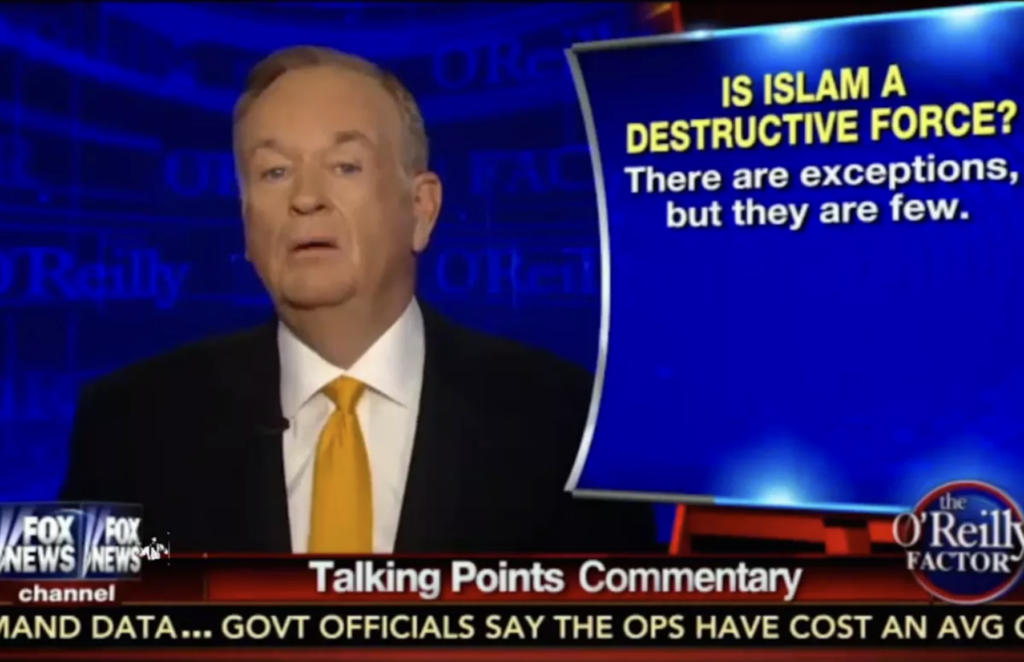

Most important, extreme anti-Muslim activists regularly appeared on the FOX News Network. FOX commentator Jonathan Hoenig said we needed to “stop having Ramadan and Iftar celebrations in the White House” and learn from our history: “The last war this country won, we put Japanese-Americans in internment camps, we dropped nuclear bombs on residential city centers. So, yes, profiling would be at least a good start. It’s not on skin color, however, it’s on ideology: Muslim, Islamist, jihadist.” FOX radio show host Mike Gallagher proposed a special line at airports where all Muslims would be forced to assemble. Bill O’Reilly declared in one of his FOX commentaries: “Is Islam a destructive force? There are exceptions, but they are few.” Brian Kilmeade of FOX & Friends suggested, “There was a certain group of people that attacked us on 9/11. It wasn’t just one person, it was one religion. Not all Muslims are terrorists, but all terrorists are Muslims.”

After FOX host Jeanine Pirro assailed Islamic terrorists, she targeted respected Muslims who had participated in interfaith religious ceremonies. “Muslims were even invited to worship at the national cathedral in Washington, DC. . . . They have conquered us through immigration. They have conquered us through interfaith dialogue.”

On Sean Hannity’s show, Brigitte Gabriel declared, “We’re talking about 300 million people who are ready to strap bombs on their bodies and blow us all up to smithereens.” While criticizing President Obama for offering praise for Islam’s achievements, FOX commentator Andrea Tantaros shifted seamlessly be- tween terrorists and Islam in general.

They’ve been doing this for hundreds and hundreds of years. If you study the history of Islam, our ship captains were getting murdered. . . . You can’t solve it with a dialogue. You can’t solve it with a summit. You solve it with a bullet to the head. It’s the only thing these people understand. And all we’ve heard from this president is a case to heap praise on this religion, as if to appease them.

And the patriarch of FOX, Rupert Murdoch himself, tweeted that even peaceful Muslims needed to be accountable for the actions of the violent radicals: “Maybe most Moslems peaceful, but until they recognize and destroy their growing jihadist cancer they must be held responsible.” Remember, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: you are responsible for ISIS.

The anti-Muslim rhetoric goes well beyond FOX, of course. Conservative talk radio, websites, and social media stars hit these same themes with, if anything, even less nuance. It’s easy to find extreme statements on the fringes of any ideology, so in fairness let’s focus on the voices with the greatest influence. According to audience size, the top conservative talk radio personalities in 2017 were Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity, Michael Savage, Glenn Beck, and Mark Levin. All of these pundits regularly blurred the lines between radical Islam, terrorists, and the Islam practiced by most American Muslims.

Rush Limbaugh, who has an audience of at least 14 million, asserted that Islam was “not even a religion” and that Americans should conflate radical Islam and Islam. “[We distinguish] Muslim terrorists from other Muslims. In a more sensible time, we did not say ‘German Nazis’—we said ‘Germans’ or ‘Nazis’ and put the burden on non-Nazi Germans, rather than on ourselves, to separate themselves from the aggressors.”

Michael Savage, who reaches more than 10 million listeners through Cumulus Media Networks, once opined, “They say, ‘Oh, there’s a billion of them [Muslims]. I said, ‘So, kill 100 million of them, then there’d be 900 million of them.’ I mean . . . would you rather us die than them?”

Mark Levin, also on Cumulus, declared that “the Muslim Brotherhood has infiltrated our government.”

Glenn Beck has simultaneously made distinctions between Muslims and Islamic extremists in one sentence and then blurred those lines in the next. When Beck hosted Keith Ellison, the first Muslim congressman, he said, “What I feel like saying is, ‘Sir, prove to me that you are not work- ing with our enemies.’” Beck added: “I’m not accusing you of being an enemy, but that’s the way I feel, and I think a lot of Americans will feel that way.” His book, It Is About Islam, explains, “In America we like to believe that all religions are equal. But that’s not the truth. A religion that believes in stoning and killing people who don’t share their views and values is not equal to the rest.”

Some of the most influential voices are on neither radio nor television. The most popular conservative website in 2017 was Breitbart.com. Here are some of its recent headlines:

“The West Vs. Islam Is the New Cold War—Here’s How We Win”

“Political Correctness Protects Muslim Rape Culture”

“6 Reasons Pamela Geller’s Muhammad Cartoon Contest Is No Different from Selma”

“Roger Stone: [Clinton Aide] Huma Abedin ‘Most Likely a Saudi Spy’ . . .”

More important, other social media platforms—including Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit—enable fringe voices to gain mainstream followings. Social media has minimized or wiped out the two primary obstacles to the spread of attacks on religious minorities—cost and social stigma. Those wanting to assail, say, Mormons or Catholics or Jews in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries could do so, but few would hear their voices unless they owned a publication and had the money to disseminate it widely, as Henry Ford did with his Dearborn Independent. Now it’s fast, free, and fun. As for social stigma, Facebook in many ways rewards people with extreme views, including hostility to Islam. Posts that evoke strong reactions, either agreement or rage, are deemed by its algorithms to be more valuable and are more widely distributed. Social media doesn’t create hate, but it certainly psychologically incentivizes it. It’s not surprising, then, that people who you’d think would be embarrassed to make bigoted comments come to believe they have important ideas to share. The following examples all involve local public officials who got in trouble for posting on Facebook:

- A member of the conservation commission of Easton, Massachusetts, posted a photo of a nuclear mushroom cloud with the headline “Dealing with Muslims . . . Rules of Engagement.”

- A member of the Board of Education in Elmwood Park, New Jersey, wrote: “Go back to your own country; America needs to get rid of people like you.”

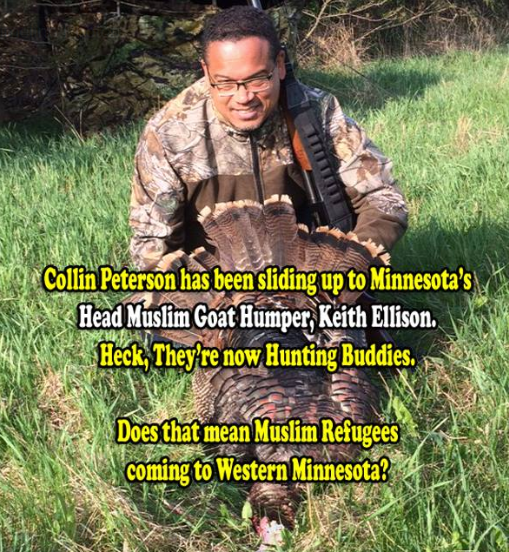

- The Minnesota Republican Party posted a photo of Minnesota congressman Keith Ellison, a Muslim, on its page, under the headline “Minnesota’s Head Muslim Goat Humper.”

- A county commissioner in Mifflin County, Pennsylvania, posted an image of a mosque with a red “No” symbol slashed through it and the headline “No Islam Allowed.”

- A Republican committee woman in California posted: “i do not want any type of muslims in our country, period! i don’t want to hear there are good muslims. look at my state of michigan. . . . stop the muslim influx!!!”

Spend time reading regular-folk posts against Muslims and you’ll spot something right away: the messages are quite similar to those espoused on talk radio, on FOX News, and by anti-Islam activists. It’s hard to prove causation, but 58 percent of Republicans who listed FOX News as their most trusted news source believed that American Muslims wanted to establish Sharia, compared with just 33 percent of Republicans who didn’t watch FOX News. Elites influence regular listeners, users, and viewers, and vice versa. It’s far easier than it used to be for public officials to have impact by attacking a minority religion. Their public statements, in turn, provide safe cover for people to voice toxic opinions that are already on the tips of their fingers. Clearly, fear drives as much of this as prejudice. Psychologically, it’s easy to drift into thinking that because many terrorists are Muslims, many Muslims are terrorists. Countering this tendency would require leaders who pour water on the fire rather than gasoline.

The President

Religious freedom has been sustained not just by laws and court rulings but also by an informal consensus that past attacks on minority religions have been so explosive, un-American, corrosive, and liable to spiral out of control that we just won’t do that anymore. When the president of the United States doesn’t demonstrate respect for that idea, the consensus can unravel quickly.

Donald Trump began airing his anti-Muslim message during his drive to prove that Barack Obama wasn’t really a US citizen. In March 2011, he said to radio host Laura Ingraham, “Now, somebody told me—and I have no idea if this is bad for him or not, but perhaps it would be—that [on his birth certificate] where it says ‘religion,’ it might have ‘Muslim.’” Later, on FOX News, he criticized Obama’s visit to a mosque: “I think that we can go to lots of places. . . . I don’t know if he’s—maybe he feels comfort- able there.” As Trump understood, partisan antipathy to Obama could be juiced if tied to anti-Muslim sentiment, and vice versa. After criticizing Obama for not attending Justice Antonin Scalia’s funeral, Trump tweeted, “I wonder if President Obama would have attended the funeral of Justice Scalia if it were held in a Mosque?”

At first, Trump’s attacks on American Muslims were indirect. On September 18, 2015, at a town hall meeting in Rochester, New Hampshire, a supporter asked: “We have a problem in this country. It’s called Muslims. Our current president is one. We know he’s not even an American. We have training camps growing where they want to kill us. That’s my question: When can we get rid of them?” When John McCain was asked a similar question in 2008, he defended Obama. Trump, by contrast, responded, “A lot of people are saying that and a lot of people are saying that bad things are happening out there. We’re going to be looking at that and a lot of different things.” His rhetoric escalated in the two months before the first primaries, a period that coincided with two terrorist attacks—the mass killing orchestrated by ISIS on November 13, 2015, in Paris and the tragedy in San Bernardino, California, on December 2, when two Muslims killed their coworkers at a Christmas party.

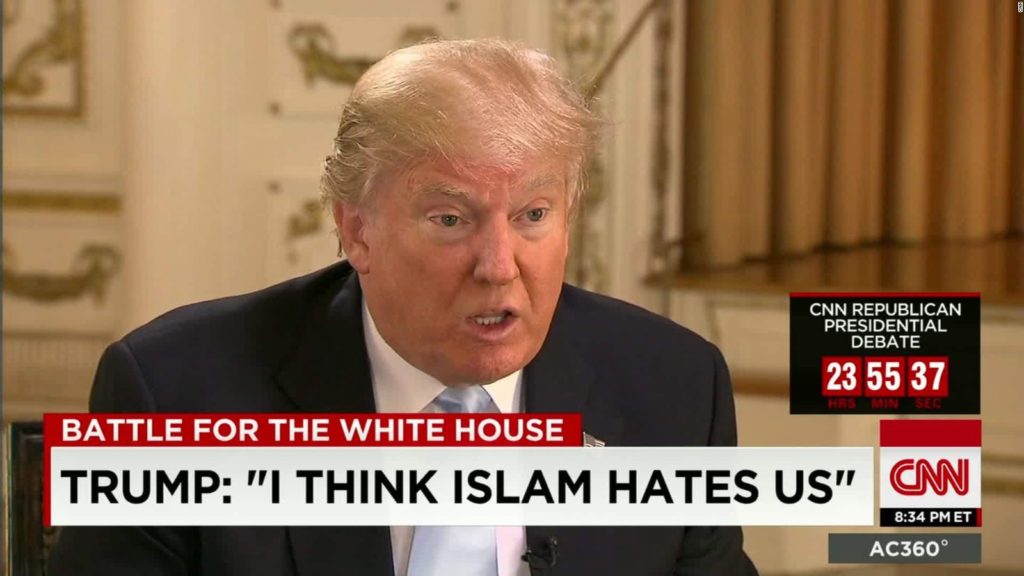

Trump deployed many of the same lines of attack used by the anti- Muslim activists. While insisting that he was going after extremists, he also routinely equated radical Islam with Islam per se. “I think Islam hates us,” he said. Asked if he meant all Muslims, he said, “I mean a lot of them. I mean a lot of them.” Just as some in earlier eras had claimed that Jews, Mormons, and Catholics would not assimilate, Trump maintained, “They come—they don’t—for some reason, there’s no real assimilation.”

Chillingly, he promoted the idea that American Muslims generally support the terrorists. While Jehovah’s Witnesses were cast as Nazi supporters during World War II, Muslims were deemed insufficiently patriotic and maybe even dangerous. Trump claimed, falsely and repeatedly, that he saw “thousands and thousands” of Muslims in New Jersey cheering the destruction of the Twin Towers on 9/11. He claimed, falsely, that American Muslims avoid reporting suspicious activity. “They’re not turning them in,” he said. He renewed the suggestion, after the San Bernardino attack, stating, falsely, “If you look at San Bernardino as an example, San Bernardino, they had bombs all over the floor of their apartment. And everybody knew it, many people knew it. They didn’t turn the people over. They didn’t do it.” (Police never found any evidence that Muslim neighbors or friends knew. The closest thing: a local news station interviewed an out-of-town visitor who claimed that a friend of his who lived near the attackers had noticed the couple working a lot in their garage and receiving large packages but didn’t report it because she didn’t want to racially profile.)

Most important, in December 2015, Trump called for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what is going on.” Gone was the idea that we should focus on Islamic fundamentalists or terrorists. No Muslims of any kind could be trusted. “It’s obvious to anybody the hatred is beyond comprehension,” said Trump.

Justifying the policy, Trump explained that Muslim refugees were “trying to take over our children and convince them how wonderful ISIS is and how wonderful Islam is.” As proof that the Muslim ban was not beyond the pale, he pointed to Franklin Roosevelt’s internment of Japanese Americans during World War II as justification. “So, you’re for internment camps?” ABC News correspondent George Stephanopoulos asked. No, he said, but “what I’m doing is no different than FDR,” who was “a president highly respected by all.”

Trump had taken the rhetorical conflation of Muslim terrorists and Muslims in general and turned it into policy. Restriction of immigration on the basis of religion was unprecedented. Although the Immigration Act of 1924 had been designed in part to reduce the number of Jews entering the country, its advocates rarely said so publicly, and that position was not championed by the president. Even in the 1830s, when anti-Catholic nativism was rampant, or in the 1920s, when the Ku Klux Klan was winning elections, successful presidential candidates did not come out and call for the banning of a particular religious group from America’s shores.

Just as stunning, Trump said he would “absolutely” require American Muslims to register in a special database to make it easier for the government to track them. “They have to be,” he said. “They have to be.” Re- porters probed for specifics, asking, for instance, whether the government would use mosques as the places to register all the Muslims. “Different places. You sign up at different places. But it’s all about management. Our country has no management.” And finally, he said that “there’s absolutely no choice” but to close down some American mosques as a way of combating extremism. “We have to be very strong in terms of looking at the mosques, you know, which a lot of people say, ‘Oh, we don’t want to do that. We don’t want to do that.’ We’re beyond that.” Asked if he would consider warrantless searches on mosques and Muslims, he said, “We’re going to have to do certain things that were frankly unthinkable a year ago.”

Nothing like this had ever been proposed by a successful presidential candidate.

Notably, to back up his proposals, Trump campaign officials cited surveys allegedly proving that a high percentage of American Muslims were radical. The surveys came from none other than Frank Gaffney, who had gone from outcast to legitimated media pundit to information source for a presidential candidate.

Public opinion about Muslims, which had been worsening for a decade, darkened as the election approached. The percentage of Republicans who said at least half of Muslims living in the United States were anti-American jumped from 47 percent in 2002 to 63 percent in 2016. (In the same poll, 92 percent of Muslims said they were “proud to be an American.”) From 2001 to 2010, 29 percent of Republicans expressed negative views of Muslims; by 2016, 58 percent did.

Trump no doubt found the political appeal irresistible. Islam-bashing drew together several distinct strains of the Republican electorate. Religious conservatives had led the charge against Islam, in part because they viewed themselves as being in a global competition with the religion. Conservative Zionists liked the toughness on Muslim majority countries that had harassed Israel. National security hawks who had criticized Obama’s alleged softness on Islamic terrorism loved Trump’s willingness to single out Islam. Opposition to Islam had filled in the gap left by the fall of Soviet Communism—providing an overarching ideological foe that could explain evil in the world and mobilize advocates of American military vigilance. That study by Whitehead, Perry, and Baker that found Trump doing especially well among those who wanted a Christian nation also reported that those same voters had high levels of animosity toward Muslims. They tended to approve of these statements: “Muslims hold values that are morally inferior to the values of people like me,” “Muslims want to limit the personal freedoms of people like me,” and “Muslims endanger the physical safety of people like me.” Trump’s antagonism toward Muslims increased his appeal to a large group of conservative Christians.

After his election, Trump appointed men allied to the most extreme anti-Muslim activists. Michael Flynn, his first national security advisor,141 was on the advisory board of Act for America, the group run by Brigitte Gabriel, whom he called “a national treasure.” (She’s the one who said that practicing Muslims cannot be loyal Americans.) Flynn dismissed Muslims’ claims that they should be protected by the First Amendment as a treacherous tactic. “It will mask itself as a religion globally because, especially in the west, especially in the United States, because it can hide behind and protect itself behind what we call freedom of religion.” And he warned that groups friendly to the terrorists had infiltrated the American government.

Steve Bannon, chief strategist during the campaign and senior advisor in the early part of the Trump administration, played a major role in promoting the anti-Muslim activists. Bannon called Frank Gaffney “one of the senior thought leaders and men of action in this whole war against Islamic radical jihad” and Pamela Geller “one of the top world experts in radical Islam and Shariah law and Islamic supremacism.”

Mike Pompeo, who would become director of the Central Intelligence Agency and later secretary of state in the Trump administration, suggested that mainstream American Muslims were soft on terrorism, un-American, or both. After two Muslim Americans exploded bombs at the Boston Marathon, every major Muslim group quickly denounced the attack, but Pompeo subsequently claimed that the “silence of Muslim leaders has been deafening” and that therefore “these Islamic leaders across America [are] potentially complicit in these acts.” He was also a frequent guest on Gaffney’s radio show between 2013 and 2016.

John Bolton, Trump’s third national security advisor, was a fan of Pamela Geller, Frank Gaffney, Robert Spencer, and other anti-Muslim activists. He endorsed Geller’s book Fatwa and Spencer’s book Stealth Jihad.148 As his chief of staff, Bolton appointed Fred Fleitz, the senior vice president of Gaffney’s Center for Security Policy, the same group that said Sharia-supporting American Muslims should not be allowed to hold public office.

Ben Carson, the brain surgeon appointed to be secretary of housing and urban development, said during his own presidential campaign that he could not support a Muslim ever being president: “I would not advocate that we put a Muslim in charge of this nation. I absolutely would not agree with that. . . . I do not believe Sharia is consistent with the Constitution of this country.” Those statements did not disqualify him from being in Trump’s cabinet.

After the election, Trump altered the Muslim ban to be a restriction on immigration from certain Muslim majority countries. The first version of the ban also included another unprecedented idea—an explicit preference for Christian refugees over Muslims, even if the lives of both groups were equally in danger. This policy would, he said, right a horrible wrong. “Do you know if you were a Christian in Syria it was impossible, at least very tough, to get into the United States? If you were a Muslim you could come in, but if you were a Christian, it was almost impossible,” Trump maintained. (Actually, from 2002 to 2015, 46 percent of refugees from Syria were Christian, while 32 percent were Muslim.)

Trump continued to use his bully pulpit to blur the lines between Muslim thugs and Muslims in general. As president, he retweeted to his 43 million followers, “video: Muslim migrant beats up Dutch boy on crutches!” The man, as it turned out, was not a migrant and most likely not a Muslim. The source of the video was Britain First, an avowedly fascist organization. Trump’s aides continued to treat Islam as if it were a curse word. In 2018, Trump’s lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, decided that an effective way to tarnish the character of former Central Intelligence Agency director John Brennan was to say that he “claims to be a great lover of Islam.”

In some ways, the attacks on American Muslims have actually revealed the strength of our modern religious freedom model. After Trump announced his “travel ban,” thousands of protestors flooded airports. The courts forced him to recast it as a prohibition on travel from a handful of Muslim countries. The courts then threw out that narrower ver- sion because it still prioritized Christian refugees over Muslims. The administration revised it again to drop the preference for Christians, add non-Muslim countries, and drop some Muslim ones. That version was approved 5–4 by the US Supreme Court. In one sense it was sad day: a policy that originated with blatant religious animus had been implemented. But there’s another way to look at it. The courts and public opinion forced the administration to play by a modern set of religious liberty rules.

There were other signs that the religious liberty apparatus was holding up. Local courts and planning boards brushed aside many efforts to block construction of mosques and Islamic cemeteries. We’ve also seen some non-Muslim religious leaders expressing farsighted solidarity. Republican senator Orrin Hatch, a conservative Mormon, defended the rights of Muslims to build the so-called ground zero mosque. After Trump floated the idea of creating a national registry of Muslims, the head of the Anti- Defamation League responded that he too would register as a Muslim. As assaults on Jews from far-right groups have increased, Muslim leaders have, in turn, shown their own solidarity. After the massacre at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh in October 2018, two Muslim groups organized a fundraiser to pay all the funeral costs of the Jewish victims.

But the attacks on Muslims still need to be taken seriously because they reflect a return to dark tendencies we thought we’d vanquished for- ever, and this bodes ill not just for Muslims but for religious freedom in general. We can see all the elements from prior bouts of persecution. A minority religion is cast as alien, foreign, undemocratic, and not a valid faith. Ethnic and religious fears blend and reinforce each other. Irresponsible press coverage spreads ignorance and fear. A previously persecuted denomination forgets its own history and turns on a new unpopular religious minority. Political leaders are rewarded rather than punished for stoking religious antagonism. The majority perceives itself as losing status and lashes out.

Popular support for religious freedom is more fragile than we thought. In December 2015, the month in which Trump was calling for a ban on Muslim immigrants and a registry, pollsters asked Republicans whether Islam should be made illegal in the United States. The results: 26 percent said Islam should be banned, and 21 percent weren’t sure. Only half of Republicans were willing to say that Islam should be legal in America.

During this same period, violent attacks on American Muslims grew.

It’s impossible to say what role the normalization of anti-Muslim rhetoric played—ISIS was increasing its horrific activity in those years too—but something shifted. Hate crimes against American Muslims in 2016 were twice as high as they were in 2014. The 2015 tally included 12 murders, 8 anti-Muslim arsons, 9 shootings or bombings (mostly of mosques), and 29 assaults. Almost one-third of the attacks in 2015 came in December as Trump’s anti-Muslim campaign hit full gear. Here’s a small sample from the final quarter of 2015:

- October 17, Bloomington, Indiana. An Indiana University student yells “Kill them all!” at a Muslim woman prior to slamming her head into a table and attempting to pull off her hijab.

- November 1, Burlington, Massachusetts. The Islamic Center is spray-painted with the letters USA.

- November 6, Coon Rapids, Minnesota. A Muslim woman dining with her family at Applebee’s has a beer mug smashed across

her face. - November 14, Meriden, Connecticut. An area mosque is shot up with bullets.

- November 16, Pflugerville, Texas. Feces are smeared on the door of the local Islamic center.

- November 19, New York City, New York. Three students assault a sixth-grade Muslim student during recess. They call her “ISIS,” punch her, and try to pull off her hijab.

- November 26, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A Muslim taxi driver is shot by a passenger asking about ISIS.

- December 1, Anaheim, California. A bullet-riddled copy of the Quran is left for the owner of Al-Farah Islamic Clothing.

- December 6, Castro Valley, California. A woman throws hot coffee at Muslims in Alameda County Park.

- December 7, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. A bloody pig’s head is placed outside the door of the Al-Aqsa Islamic Society.

- December 7, Vandalia, Ohio. While riding on a school bus, a seventh grader threatens to shoot a Muslim schoolmate, calling him “towel head,” “terrorist,” and “son of ISIS.

- December 10, Coachella Valley, California. A mosque is fire- bombed.

- December 13, Hawthorne, California. Vandals deface two mosques, writing “Jesus is the way” on one of them.

- December 13, Grand Rapids, Michigan. A robber calls a convenience store clerk “terrorist” and then shoots him in the face.

- December 24, Richardson, Texas. A shooter yells “Muslim!” as he murders one man and injures another.

Nazar Naqvi was one American Muslim who could not understand why his people have become the objects of such rage in the past fifteen years. “Why are we Muslims being blamed for something done by 19 people? Why? Why is that? We are patriotic Americans.” His plaintive questions were posed during his visit to Evergreen Memorial Park in Colonie, New York. His son, Mohsin, is buried there. Mohsin was killed in Afghanistan in 2008, having signed up for the US Army four days after 9/11.