The Religious Freedom of Slaves

African spirituality and Islam are purged, creating a “spiritual holocaust.”

Discussions of religious liberty before the Civil War rarely consider the status of African Americans for an understandable but perverse reason: their subjugation was so thorough that the loss of their religious freedom seemed to be the least of their problems. But if anything, depriving them of their faith as they tried to endure slavery was especially cruel. While Americans have held up religious liberty as sacred, we have repeatedly declined to offer it to those we viewed as subhuman. The slave experience also showed that when other freedoms are curtailed, religious liberty suffocates as well.

In all, about 455,000 Africans were brought to the United States as slaves, 388,000 directly from Africa and the rest via the Caribbean. Historians debate the extent to which slaves in America were discouraged from practicing Christianity—but that question skips a step. The vast majority had practiced indigenous African religions or Islam, not Christianity, before they were kidnapped. Traces of African religion have persisted through the generations via African American music, dance, and other cultural practices. But while African spirituality partly survived as culture, it mostly did not survive as religion. Between the 1680s and 1860, slaves “experienced a spiritual holocaust that effectively destroyed traditional African religious systems,” wrote historian Jon Butler. Albert Raboteau, one of the preeminent scholars of slave religion, noted that African traditions persisted more successfully in Cuba, Haiti, Brazil, and other countries with large slave populations. “In the United States,” he wrote, “the gods of Africa died.”

The first thing to understand about African religion is that it existed. Slaves in America were often thought to have no religion or an ad hoc collection of superstitions. But while they did come from different regions and tribes, there were shared elements. They tended to believe in a High God, a Supreme Creator who was removed from day-to-day earthly doings, which were controlled by lesser gods and ancestor spirits. They believed in reincarnation and revered the elderly in part because they helped preserve the memory of the dead. Music, dance, and medicine cured the soul as well as the body. “The religious background of the slaves was a complex system of belief,” wrote Raboteau, “and in the life of an African community there was a close relationship between the supernatural, the secular and the sacred.”

By breaking up families, slavery thwarted the preservation of their religion. Young men were taken from the mothers and grandmothers, who had been the primary keepers of ancestral memory and traditions. Slave purchasers often avoided taking African spiritual leaders, who would be troublemakers and poor laborers. Masters usually prevented five or more slaves from gathering at a time, making religious rituals difficult to sustain except in secret. Slaves were forbidden from speaking African languages. After the end of slave importation in 1808, the slave population in America grew mostly through reproduction. With each generation, knowledge and commitment to African traditions faded. By the way, there is no evidence that James Madison, the foremost champion of religious freedom, sought such rights for his own slaves.

This in no way diminishes the importance of Christianity in sustaining African Americans during the slave period. Moreover, had slavery never existed, many might well have voluntarily chosen Christianity in Africa. But most Africans had no such choice. To better fathom the consequences, consider this thought experiment. More than 30 million living African Americans are descended from slaves. If their ancestors had been able to maintain the faith of their ancestors, and those traditions had been passed down, African religions—the spirituality of the Akan, Ashanti, Dahomean, Ibo, and Yoruba societies—would be as significant in the United States today as Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism combined.

Muslim American Slaves

About 10 percent of the slaves—hundreds of thousands of people—were Muslims,6 meaning that at the time of the country’s founding, there were probably more Muslims in America than Jews or Catholics.

The first Muslims to live in America were brought as slaves in the seventeenth century by the Spanish Catholics. But most came later as part of the slave trade with West Africa, including the Sokoto Caliphate in modern-day Nigeria and Cameroon and an area called Senegambia in modern-day Senegal and Gambia (Gambia today is 90 percent Muslim).

Many historical fragments confirm the presence of practicing Muslim slaves in the United States. An advertisement in Savannah, Georgia, sought the return of some runaway slaves with Muslim names, while an ad in the Charleston Courier described a runaway named Sambo “who writes the Arabic language.” George Washington in 1784 listed in his ledger the names “Fatimer” and “Little Fatimer,” a mother and daughter almost certainly named after Muhammad’s daughter Fatima. Interviews with slave descendants in Georgia in the 1930s turned up several descriptions of Muslim prayer practices. Rosa Grant described her grandmother Ryna: “Every morning at sun-up she kneel on the floor in a room and bow over and touch her head to the floor three time. Then she say a prayer. . . . When she finish praying, she say, ‘Ameen, ameen, ameen.’” A slave, Bilali Mohamed, had daughters named Medina and Margaret. Margaret would, according to her granddaughter, pray on a special “little mat to kneel on.” She “was very particular about the time they pray and they were very regular about the hour; [they prayed] when the sun come up, when it straight over the head, and when it set.” Ed Thorpe remembered that his grandmother, Patience Spalding, would “bow her head down three times and say ‘Ameen, Ameen, Ameen.’”

In a few unusual cases, Muslim slaves became celebrities of sorts, usually because they converted to Christianity or seemed unusually learned. One named Abd al-Rahman had apparently owned two thousand slaves as a nobleman in Africa before he became a slave himself in the United States. John Quincy Adams and others championed his case because he’d supposedly become Christian. Others pretended to embrace Christianity while secretly maintaining their religion. Omar ibn Said, a slave in North Carolina, was said to have converted in 1819, yet his autobiography, written in 1831, begins “In the name of God, the merciful, the compassionate. May God bless our Lord Mohammad.” In some cases, the blending of faiths was not trickery as much as syncretism, an organic mixing of traditions. A priest commented that “the Mohammedan African” slaves had been known to accommodate Christianity to Islam: “God, say they, is Allah, and Jesus Christ is Mohammed—the religion is the same.”

The disappearance of Islam happened through some combination of coercion, pressure, and voluntary spiritual choices. A Muslim slave in Mississippi noted to a merchant, “in terms of bitter regret, that his situation as a slave in America, prevents him from obeying the dictates of his religion. He is under the necessity of eating pork, but denies ever tasting any kinds of spirits.” The normal means for passing Islam from one generation to the next—Quranic schools, mosques, and regular readings from the Quran—were not allowed. Families were routinely broken up, so “the chances for a Muslim man to find a Muslim spouse, have children, and keep them long enough to pass on the religion were indeed slim,” wrote historian Sylviane A. Diouf in Servants of Allah. Finally, to the ex- tent that slaves were allowed to have religion, it needed to be Christianity. In fact, a Virginia law required that slaves—“whether Negroes, Moors, Mollattoes or Indians . . . shall be converted to the Christian faith.”

“Glad Tidings to the Poor Bondman”

After 1800, the Second Great Awakening energized Christianity among slaves. The evangelical emphasis on a personal conversion experience and having a direct relationship with God made the Bible more accessible to illiterate slaves. One former slave explained its appeal.

It brought glad tidings to the poor bondman; it bound up the broken-hearted; it opened the prison doors to them that were bound, and let the captive go free. As soon as it got among the slaves, it spread from plantation to plantation, until it reached ours, where there were but few who did not experience religion.

Some of the religious activity happened in recognized churches. Converting slaves on plantations became a cause for outside missionaries and pious Christians throughout the South. Some whites believed that Christianity would make slaves more obedient. Others hoped that it would give a noble aura to the institution of slavery itself, as it could be seen as a way of elevating the hapless African. Many slaves attended the churches of their masters, but some independent black churches survived too. A few grew so strong that they could raise money to buy members’ freedom. From 1846 to 1861, the Methodist Episcopal Church saw its black member- ship rise from 118,904 to 209,836. Black Baptists, by one estimate, grew from 40,000 in 181327 to 200,000 in 1846 to 400,000 in 1860.

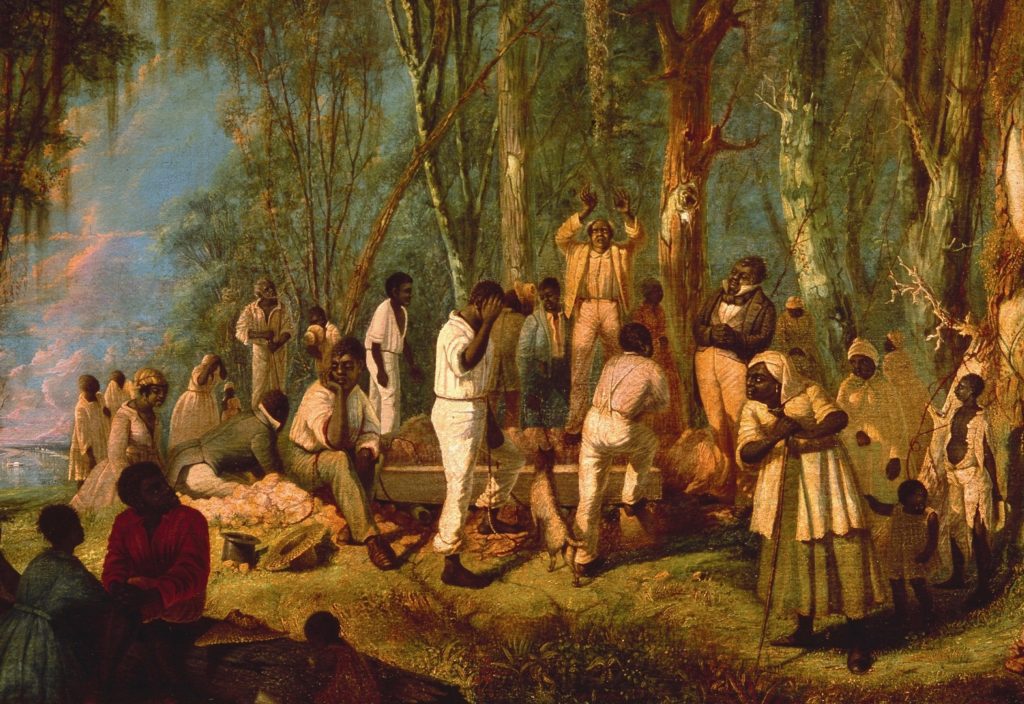

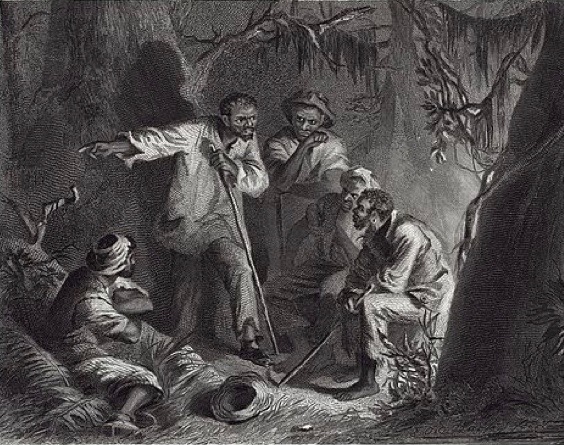

But because the preaching in approved churches was geared toward the teaching of obedience, slaves often came to resent it. Underground religion developed. They would gather secretly in “hush harbors” in the woods—“singing and praying while huddled behind quilts and rags, which had been thoroughly wetted ‘to keep the sound of their voices from penetrating the air,’” as one former slave recalled. At these secret revivals and prayer meetings, “the slave forgets all his sufferings,” a slave recalled, “except to remind others of the trials during the past week, exclaiming, ‘Thank God, I shall not live here always!’” Some religious services offered the promise that they or their children would see freedom (“I know that some day we’ll be free and if we die before that time, our children will live to see it,” as one slave put it). Others emphasized the freedom awaiting them in the next life. When describing how an overseer had set vicious dogs on his mother, a slave explained, “She died soon after, and was freed from her tormentors, at rest from her labors, and rejoicing in heaven.”

Since slave masters feared the insurrectionist potential of religion, the very act of worshipping was a form of rebellion. “The white folks would come in when the colored people would have a prayer meeting, and whip every one of them,” recalled one slave. A black preacher named G. W. Offley liked to tell the story of a slave he called “Praying Jacob.” This man prayed in the fields three times a day. His master said that if he did it again he’d blow his brains out. Jacob told him to shoot away.

Your loss will be my gain. I have two masters, one on earth and one in heaven—master Jesus in heaven, and master Saunders on earth.

I have a soul and a body; the body belongs to you, master Saunders, and the soul to Jesus.

When the charismatic Reverend Turner first began preaching in the fields of Southampton County, Virginia, he urged the slaves to obey their masters, assuring them that their liberation would come in the hereafter. But that changed after he had apocalyptic visions. In 1825, he saw “white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle, and the sun was darkened—the thunder rolled in the Heavens, and blood flowed in streams.” A few years later, he “heard a loud voice in the heavens, and the Spirit instantly appeared to me and said the Serpent was loosened, and Christ had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it and fight against the serpent.” His interpretation: the serpent was slavery, and it must be destroyed. “The time was fast approaching,” he said, “when the first should be last and the last should be first.”

And so, on August 21, 1831, the Reverend Nat Turner led sixty fellow slaves in a rebellion, killing more than fifty-five whites, including twenty- five children.

The white population’s long-standing fears of a slave insurrection had finally come true. Why had it happened? What could be done to prevent it from ever happening again? John Floyd, the governor of Virginia, knew where to lay the blame: the Yankees who came South and made the slaves religious, telling the blacks [that] God was no respecter of persons—the black man was as good as the white man—that all men were born free and equal—that they cannot serve two masters—that the white people rebelled against England to obtain freedom, so have the blacks a right to do.

In Floyd’s view, Southern whites—both “our females and the most respectable”—came to think that piety required teaching the Negroes to read and write so they could absorb scripture. Before long, these naïve do-gooders were passing out incendiary pamphlets “from the New York Tract Society.” Finally, the black preachers, both freed and slave, read abolitionist tracts from the pulpit. “The Northern incendiaries, tracts, Sun- day Schools, religion and reading and writing has accomplished this end,” Floyd explained.

Southerners knew this wasn’t the first time that religion had been implicated in a slave uprising. Denmark Vesey, who ostensibly plotted a rebellion in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1822, had recruited most of his comrades from the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, which had been created by the small community of freed blacks. After the inci- dent, the church was burned to the ground and nineteen of its members were arrested. (Hauntingly, it was at that same church, rebuilt, that a white supremacist gunman named Dylann Roof massacred black parishioners in June 2015.) In 1800, a slave named Gabriel near Richmond, Virginia, organized a plot among thousands of slaves, using religious meetings to coordinate and Bible passages to motivate.

So, when the Nat Turner rebellion occurred, Southern governors did not hesitate to attack the religious freedom of slaves. South Carolina banned black churches. Virginia forbade slaves and free blacks from conducting religious meetings. They could attend only gatherings led by white preachers, during the day, after getting permission from their masters. North Carolina decreed that free Negroes could not preach. Alabama prohibited any assembly of five or more blacks and required that they could preach only if five “respectable slave-holders” were present. In Louisiana, an earlier law provided the death sentence for ministers who used their pulpits to “produce discontent” among slaves or free blacks. As a teenage slave in Maryland, Frederick Douglass had been asked to help teach “Sabbath School” to other slaves. But after word spread, several slave owners stormed the meeting and declared that Douglass apparently “wanted to be another Nat. Turner, and that, if I did not look out, I should get as many balls in me as Nat. did into him. Thus ended the Sabbath-school.”

Religious rights, it became clear, do not exist in isolation. Eliminating other basic liberties—especially freedom of expression, speech, assembly, and press—invariably undercuts religious freedom too. Attacks on one right will degrade others. Dehumanization was the predicate to regulation. If slaves weren’t people, then masters could avoid the cognitive dissonance of being God-fearing Christians who prevent slaves from worshipping God. Douglass noted the irony: “Think of a body of men thank- ing God every Sabbath-day that they live in a country where there is civil and religious freedom . . . [even while] there are three millions of people herded together in a state of concubinage, denied the right to learn to read the name of the God that made them.”